If I recall correctly, a few years back, Barbie(TM) was subject to an enormous amount of criticism for suggesting that math is hard. I always thought this unfair. The Pithlord is not afraid to admit that he sometimes finds topology and complex analysis a bit counter-intuitive, and he doesn't see why a blonde plastic doll shouldn't be allowed to exchange her frank views on the subject with her admirers -- many of whom, I suspect, agreed with her.

But the Pithlord is a bit dismayed that the brilliant "libertarian" legal minds at the Volokh Conspiracy think that the issues raised in the Military Commissions Bill are beyond their ken.

In this post Orin Kerr, an expert in privacy and search law, modestly expresses "an appropriate awareness of [his] limitations." This modesty, however becoming, seems inappropriate. Kerr obviously has strong views about how much judicial scrutiny should be given to entering people's houses, tapping their phones and so on. Complicated stuff, but I bet the answer is more than none.

Eugene Volokh exceeds even Professor Kerr in modesty. Volokh is a highly-regarded free speech expert, if a bit absolutist for my taste. Apparently, the complete absence of judicial supervision of executive detainment and interrogation is too tricky for his intellect.

Codswallop.

Friday, September 29, 2006

Hands Off Thucydides!

Henry Farrell gets medieval on a pet peeve of mine: neoimperialists invoking Thucydides. I'm not a big fan of our pundit Blavatskys who tell us that the dead would be on their side of some contemporary controversy. Orwell gets this the most of course. But if I was going to pick a historical figure supportive of democratic imperialism and the remote social engineering implied in transforming the Islamic world into a swarthier Kansas, then Thucydides would be absolutely the last on any list.

Wednesday, September 27, 2006

Blogging Will Be Light

Gotta work on something else. In the meantime, I thought I would point you to this hurtful and offensive, but funny and well-informed column about our difficulties in Afghanistan with the wily Pathan, and how the British empire of old would have handled it.

Tuesday, September 26, 2006

The Trouble With "Party Democracy"

It looks like the Volpe and Ignatieff camps have been signing up the undead as Liberals. It's not good for a party that has to improve its ethical image.

Truth is that every party has contested leadership campaigns of the kind you would expect if LBJ and Mayor Daley were running for President of a central African country. The electorate is elastic, there are no real referees and intra-party quarrels are always the nastiest.

Even if they were squeaky clean, though, we would still face the normatively-unacceptable reality that our choices for high office are limited to those chosen by self-selected partisans. Further, once selected, there is rarely a legitimized way of deposing the leader, although deposition is often warranted.

Frankly, the whole system seems unconstitutional to me. Her Majesty's government should be led by the person with the confidence of a majority of the House, not the person selected by the bizarre rituals of a political party. Only the government caucus has the legitimacy to select their leader (and the continuing existence necessary for the inevitable regicide).

Sadly, the misguided "democratic" notion that a bigger electorate is always a better one will just lead us to direct election by party members, which is more boring and no more legitimate than the kind of brokered convention we will see for the Libs.

Truth is that every party has contested leadership campaigns of the kind you would expect if LBJ and Mayor Daley were running for President of a central African country. The electorate is elastic, there are no real referees and intra-party quarrels are always the nastiest.

Even if they were squeaky clean, though, we would still face the normatively-unacceptable reality that our choices for high office are limited to those chosen by self-selected partisans. Further, once selected, there is rarely a legitimized way of deposing the leader, although deposition is often warranted.

Frankly, the whole system seems unconstitutional to me. Her Majesty's government should be led by the person with the confidence of a majority of the House, not the person selected by the bizarre rituals of a political party. Only the government caucus has the legitimacy to select their leader (and the continuing existence necessary for the inevitable regicide).

Sadly, the misguided "democratic" notion that a bigger electorate is always a better one will just lead us to direct election by party members, which is more boring and no more legitimate than the kind of brokered convention we will see for the Libs.

Sunday, September 24, 2006

What We Knew

William snapped, "Drop it; we're looking for a Greek book!"

"This?" I asked, showing him a work whose pages were covered with abstruse letters. And William said: "No, that's Arabic, idiot! Bacon was right: the scholar's first duty is to learn languages!"

"But you don't know Arabic either!" I replied, irked, to which William answered, "At least I know when it is Arabic!"

--Umberto Eco, The Name of the Rose

Like most people who opposed the Iraq war, the Pithlord is constantly accosted by chastened righties I argued with back in 2003 who cry, "You were right! The Iraq war was a terrible idea! How do I correct my worldview so I don't make mistakes like that again?"

We at Pith and Substance are always anxious to help. And since everyone who can be convinced has now been, I am willing to let my rightie bretheren in on a secret: I didn't really know anything about Iraq either! I talked to a few emigrés -- I read Makiya. But I don't know Arabic. I had never been to Iraq. My grasp of Shi'ite theology is superficial. For reasons that escape me now, I did read the Ba'athist constitution once, but sub-Leninist blather is not very informative.

I'm sure I wasn't alone among those skeptical of the war. Indeed, a few of my comrades in the anti-war movement were astonishingly ignorant even by my standards.

So how did we get it right? We couldn't read the folkways of Iraq, but we knew that, whatver they were, they were the folkways of Iraq, of an alien culture in a civilization with good reasons to dislike and distrust us. In the unlikely event democracy held there, it would necessarily be in conflict with external occupiers.

The great benefit of conventional morality --compared with utilitarianism, for example -- is that it tells you what to do under uncertainty. Grand schemes have many more ways of going wrong than going right. Don't back down from a fight, but don't start one either. It isn't much to know, but it would have been enough.

Friday, September 22, 2006

Well Done, Sir

As Jim Henely explains, blogger Radley Balko has been instrumental in saving the life (at least for now, and hopefully forever) of Cory Maye.

Balko's original account of the case is here. Since then, he's done all he can to save the man's life. And today, it bore some fruit.

Balko's original account of the case is here. Since then, he's done all he can to save the man's life. And today, it bore some fruit.

Rule of the Median, not the Majority

Matthew Shugart makes the important point that proportional representation empowers the centre of the polity. (He does not point out, although it is equally true and equally in PR's favour, that it simultaneously allows the extremes to articulate why the centre should change.) To a lesser extent, this is the merit of democracy more generally.

The majority is a scary, violent thing -- but the middle is not. The most attractive face is the median face. While the median position may not be the best, in the abstract, it will be the least divisive one to take. Since the median voter is not an actual person, but a statistical abstraction, her rule is the least tyrannical rule.

Indeed, after much thought on the subject, I prefer the rule of the median voter even to the rule of the Pithlord. The Pithlord is trying to be a pundit -- he is trying to say interesting things. Interesting things must, of necessity, be wrong more often than uninteresting things. And it is through dull language that we must be ruled.

The language of democratic rule cannot be one of pith, or of substance, but of careful verbosity. For all the talk of the "soundbite" era, as Kinsley pointed out, memorable one-liners by politicians are most often career-enders: "Money and the ethnic vote"; "Maritimers should compare their situation to that of Bangladesh"; "An election campaign is no time to discuss important matters of public policy"; "Why should I sell your wheat?" The favourably received one-liners ("Just watch me"; "I paid for this microphone"; "There you go again") are moronic family sit-com fodder. Clinton -- by all accounts a brilliant man -- only memorable utterance was the question of what the meaning of is is.

That's fine. A peaceful kingdom is not ruled by clear thought. Pity the nation when prose stylists -- Trotskys or Churchills -- come to power.

And it is also fine when we are ruled by a decision rule as excruciatingly dull as the empowerment of the median voter. Someday such a person may absorb a confused and watered down version of the conceptual revolutions of a generation ago -- of environmentalism, of feminism, of public choice theory and sociobiology. It is the confusion and watering-down that saves us from the totalitarian nightmare all lucid thinkers would impose on us.

The majority is a scary, violent thing -- but the middle is not. The most attractive face is the median face. While the median position may not be the best, in the abstract, it will be the least divisive one to take. Since the median voter is not an actual person, but a statistical abstraction, her rule is the least tyrannical rule.

Indeed, after much thought on the subject, I prefer the rule of the median voter even to the rule of the Pithlord. The Pithlord is trying to be a pundit -- he is trying to say interesting things. Interesting things must, of necessity, be wrong more often than uninteresting things. And it is through dull language that we must be ruled.

The language of democratic rule cannot be one of pith, or of substance, but of careful verbosity. For all the talk of the "soundbite" era, as Kinsley pointed out, memorable one-liners by politicians are most often career-enders: "Money and the ethnic vote"; "Maritimers should compare their situation to that of Bangladesh"; "An election campaign is no time to discuss important matters of public policy"; "Why should I sell your wheat?" The favourably received one-liners ("Just watch me"; "I paid for this microphone"; "There you go again") are moronic family sit-com fodder. Clinton -- by all accounts a brilliant man -- only memorable utterance was the question of what the meaning of is is.

That's fine. A peaceful kingdom is not ruled by clear thought. Pity the nation when prose stylists -- Trotskys or Churchills -- come to power.

And it is also fine when we are ruled by a decision rule as excruciatingly dull as the empowerment of the median voter. Someday such a person may absorb a confused and watered down version of the conceptual revolutions of a generation ago -- of environmentalism, of feminism, of public choice theory and sociobiology. It is the confusion and watering-down that saves us from the totalitarian nightmare all lucid thinkers would impose on us.

The Patron Rabbi of Blogging

Via Harold Bloom, hear the words of Rabbi Tarphon:

Indeed. Heh. Read the whole thing.

Happy New Year to our Jewish readers!

You are not required to complete the work, but neither are you free to desist from it.

Indeed. Heh. Read the whole thing.

Happy New Year to our Jewish readers!

Analogies: Cold War and Jihad

A month ago, Ross Douthat wrote a piece in the Wall Street Journal cleverly dividing pundit opinion on whatever-we-are-currently-calling-the-conflict-with-Islamic-nutbars based on the year the pundit thinks it is. Most familiar from bar debates is 1938, the year of the Munich agreement between Chamberlain and Hitler, but Douthat pointed to partisans of 1914, 1919, 1941, 1948 and 1972.

Analogies to Hitler and fascism flow freer than cheap beer at a frat party, but analogies to the Cold War have the advantage of being (somewhat) predictive. If a person is the sort of person who was a dove in the Cold War, then the probability that they are a dove now is >.5, and mutatis mutandis for hawks. We can all think of interesting counter-examples, but that's the way to bet.

Which is interesting, because in the Cold War, there were really two cross-cutting fights. We don't talk about it much nowadays, but there really were people in the West who sympathized with the other side. They were never as numerous in the English-speaking world s in Italy or France (where the Communist Parties were the principal vehicle of industrial working class politics), but a substantial group of intellectuals were in or around the CPs up to 1956. After '56, outright preference for the USSR became an eccentric thing in the Anglosphere, and the Western European parties drifted towards Eurocommunism, irrelevance or both. But lots of people were inspired by Leninist revolutions and revolutionaries in less melanin-deficient places. Even now, we still see this about Cuba from the likes of Sacha Trudeau.

To any thinking person, that debate ought to have been resolved long ago. Even to the unthinking, 1989 settled it. Communism sucked. It was unbelievably murderous, destructive of human freedom, culture and virtue, and was just plain awful and grey. Those who hated it were absolutely vindicated.

But there was another debate, in which neither side was so definitively shown to be right. This debate was (or ought to have been) confined to those who wanted to resist Communist encroachment. It was whether the Communist states and movements should be viewed as roughly rational actors, with their own interests, and much less monolithic than they seemed, or whether they should simply be fought as hard as possible at every opportunity. Very right wing people -- George Kennan and Enoch Powell, for example -- saw the Soviet Union in its external dimension as willing to play the great power game. They thought it should be treated roughly like Tsarist Russia -- potentially dangerous, but with its own legitimate interests. Domestically, a number of politicians knowingly blocked with Communists for limited purposes, and won out: Roosevelt and Mitterand come to mind. Nixon going to China is the perfect metonym for this tendency, although Churchill going to Moscow would do as well. Both of these examples involved devoutly anti-communist politicians finding common interests with Mao and Stalin themselves.

The original neo-conservative intervention in international politics was not against sympathizers with the Communist system, but against those willing to make pragmatic deals. In this, the neo-conservatives joined the earlier fusionist right. But the neoconservatives turned out to be wrong: wrong that a "totalitarian" nation, unlike an authoritarian one, could never undergo internal change and wrong about the military size of the threat.

One key difference between now and then is that the jihadists are not very much like the Leninists. Another is that only the strategic/tactical debate exists in the West (outside the Muslim enclaves within it). There just are no sympathizers of the jihadis among secularists, Christians, Jews, Hindus or Buddhists. They don't exist. But much of the polemic used by the neoconservatives, the template for which was developed in the Cold War, ignores this.

Analogies to Hitler and fascism flow freer than cheap beer at a frat party, but analogies to the Cold War have the advantage of being (somewhat) predictive. If a person is the sort of person who was a dove in the Cold War, then the probability that they are a dove now is >.5, and mutatis mutandis for hawks. We can all think of interesting counter-examples, but that's the way to bet.

Which is interesting, because in the Cold War, there were really two cross-cutting fights. We don't talk about it much nowadays, but there really were people in the West who sympathized with the other side. They were never as numerous in the English-speaking world s in Italy or France (where the Communist Parties were the principal vehicle of industrial working class politics), but a substantial group of intellectuals were in or around the CPs up to 1956. After '56, outright preference for the USSR became an eccentric thing in the Anglosphere, and the Western European parties drifted towards Eurocommunism, irrelevance or both. But lots of people were inspired by Leninist revolutions and revolutionaries in less melanin-deficient places. Even now, we still see this about Cuba from the likes of Sacha Trudeau.

To any thinking person, that debate ought to have been resolved long ago. Even to the unthinking, 1989 settled it. Communism sucked. It was unbelievably murderous, destructive of human freedom, culture and virtue, and was just plain awful and grey. Those who hated it were absolutely vindicated.

But there was another debate, in which neither side was so definitively shown to be right. This debate was (or ought to have been) confined to those who wanted to resist Communist encroachment. It was whether the Communist states and movements should be viewed as roughly rational actors, with their own interests, and much less monolithic than they seemed, or whether they should simply be fought as hard as possible at every opportunity. Very right wing people -- George Kennan and Enoch Powell, for example -- saw the Soviet Union in its external dimension as willing to play the great power game. They thought it should be treated roughly like Tsarist Russia -- potentially dangerous, but with its own legitimate interests. Domestically, a number of politicians knowingly blocked with Communists for limited purposes, and won out: Roosevelt and Mitterand come to mind. Nixon going to China is the perfect metonym for this tendency, although Churchill going to Moscow would do as well. Both of these examples involved devoutly anti-communist politicians finding common interests with Mao and Stalin themselves.

The original neo-conservative intervention in international politics was not against sympathizers with the Communist system, but against those willing to make pragmatic deals. In this, the neo-conservatives joined the earlier fusionist right. But the neoconservatives turned out to be wrong: wrong that a "totalitarian" nation, unlike an authoritarian one, could never undergo internal change and wrong about the military size of the threat.

One key difference between now and then is that the jihadists are not very much like the Leninists. Another is that only the strategic/tactical debate exists in the West (outside the Muslim enclaves within it). There just are no sympathizers of the jihadis among secularists, Christians, Jews, Hindus or Buddhists. They don't exist. But much of the polemic used by the neoconservatives, the template for which was developed in the Cold War, ignores this.

A King Over the Water?

As long-time readers know, when I want to know what real black-hearted reactionaries are thinking, I go over to Daniel Larison's site. A few points reduction in marginal tax rates are pretty small potatoes compared to the restoration of medieval Christendom.

Larison points out that the intervention of the king of Thailand helped ensure that the recent coup went off bloodlessly. (Disclaimer: the Pithlord knows nothing about Thai politics) This is another example of the advantages of constitutional monarchies -- an individual not directly involved in politics can represent the continuity of the state and of the nation. He concluded, "Monarchy is not suited to all places and all peoples, just as democracy is not, but King Bhumibol gives us a glimpse of what a good monarchy might look like."

One of his commenters took exception to this atypical wetness, arguing that monarchy is always and everywhere the preferable form of government, and the Great Republic's failure to assert that (notwithstanding an odd desire to place close kin of past Presidents in executive office) is "inseparable from the corrosive liberalism that besets the nation."

I pointed out that American monarchists would face the difficulty of agreeing on the appropriate dynasty, with professional sports figures and Hollywood lineages having more-than-colourable claims. "Gabriel" declared, in true Tory style, that the Jacobite line is tanned and rested, and that, after all, without any of that bad blood about stamp taxes and tea duties poisoning relations with the Hanoverians.

One might well argue that a Franco-Scottish nation like Canada should give the Jacobite line (now with the royal house of Bavaria, if I am not mistaken) a look. In 2003, Tony O'Donohue, a former Toronto alderman, brought a constitutional challenge to the Act of Succession on the grounds it discriminates on the basis of religion by denying succession to the throne to Catholics. It does, of course, but the court sensibly declared that it is part of the constitution itself, and therefore s. 15 of the Charter does not apply.

Had it been different, though, and had the court been willing to remedy the discrimination back to its 17th century roots, and had Duke Franz been willing to take on the task of being Francis I of Canada, we would have our own monarchical line.

As Ontario Protestant in origin, I can't be expected to support all this, but I do agree with Andrew Coyne that we should get our own cadet branch of the Windsors. (Cadet lines for allied countries has a long tradition -- from the Austrian Hapsburgs to the Spanish Bourbons). We could adopt gender- and religion-neutral succession rules.

Larison points out that the intervention of the king of Thailand helped ensure that the recent coup went off bloodlessly. (Disclaimer: the Pithlord knows nothing about Thai politics) This is another example of the advantages of constitutional monarchies -- an individual not directly involved in politics can represent the continuity of the state and of the nation. He concluded, "Monarchy is not suited to all places and all peoples, just as democracy is not, but King Bhumibol gives us a glimpse of what a good monarchy might look like."

One of his commenters took exception to this atypical wetness, arguing that monarchy is always and everywhere the preferable form of government, and the Great Republic's failure to assert that (notwithstanding an odd desire to place close kin of past Presidents in executive office) is "inseparable from the corrosive liberalism that besets the nation."

I pointed out that American monarchists would face the difficulty of agreeing on the appropriate dynasty, with professional sports figures and Hollywood lineages having more-than-colourable claims. "Gabriel" declared, in true Tory style, that the Jacobite line is tanned and rested, and that, after all, without any of that bad blood about stamp taxes and tea duties poisoning relations with the Hanoverians.

One might well argue that a Franco-Scottish nation like Canada should give the Jacobite line (now with the royal house of Bavaria, if I am not mistaken) a look. In 2003, Tony O'Donohue, a former Toronto alderman, brought a constitutional challenge to the Act of Succession on the grounds it discriminates on the basis of religion by denying succession to the throne to Catholics. It does, of course, but the court sensibly declared that it is part of the constitution itself, and therefore s. 15 of the Charter does not apply.

Had it been different, though, and had the court been willing to remedy the discrimination back to its 17th century roots, and had Duke Franz been willing to take on the task of being Francis I of Canada, we would have our own monarchical line.

As Ontario Protestant in origin, I can't be expected to support all this, but I do agree with Andrew Coyne that we should get our own cadet branch of the Windsors. (Cadet lines for allied countries has a long tradition -- from the Austrian Hapsburgs to the Spanish Bourbons). We could adopt gender- and religion-neutral succession rules.

Republican Party Unites to Make Geneva Conventions Unenforceable

According to torture law expert Marty Lederman, the McCain faction and the White House have agreed on a draft bill with this provision:

Update: Here's the link to the text of the compromise. I suspect that most courts will consider "proceeding" here to mean "civil proceeding", and criminal liability will not be eliminated. (Mind you, that requires somebody to prosecute.) If you read publisu, you will see that those up the chain-of-command will be exempt from liability unless it can be shown that they "conspired to commit" the act of torture.

Also, the President can promulgate exceptions (safe harbour acts that are "non-torture") through administrative regulations. I wouldn't be against this, although such regulations should be reviewable for complaince with the Geneva Convention. It appears they would be reviewable under the Eighth Amendment.

Second Update Matthew Shugart points out, in the comments, that the LA Times has portrayed this as a Bush capitualtion to McCain.

There is some truth to this. The substantive provisions criminalizing torture are basically the same as in the McCain bill, and I could live with them. It is the restriction on processes that could effectively hold the executive branch to these provisions that is worrisome. Restrictions on habeus were part of the McCain-Graham bill anyway -- this just ties it that much tighter.

From an international perspective, the compromise will almost certainly be acceptable to America's allies. They don't want Congress explicitly legalzing behaviour prohibited by the Common Article 3, but they aren't going to be fussed about blocking court review. I expect there is a bit of a sigh of relief among the OECD diplomatic types.

On the other hand, the American courts may be fussed. We will see how the inevitable constitutional challenges work out.

no person may invoke the Geneva Conventions or any protocols thereto in any habeas or civil action or proceeding to which the United States, or a current or former officer, employee, member of the Armed Forces, or other agent of the United States, is a party as a source of rights, in any court of the United States or its States or territories.

Update: Here's the link to the text of the compromise. I suspect that most courts will consider "proceeding" here to mean "civil proceeding", and criminal liability will not be eliminated. (Mind you, that requires somebody to prosecute.) If you read publisu, you will see that those up the chain-of-command will be exempt from liability unless it can be shown that they "conspired to commit" the act of torture.

Also, the President can promulgate exceptions (safe harbour acts that are "non-torture") through administrative regulations. I wouldn't be against this, although such regulations should be reviewable for complaince with the Geneva Convention. It appears they would be reviewable under the Eighth Amendment.

Second Update Matthew Shugart points out, in the comments, that the LA Times has portrayed this as a Bush capitualtion to McCain.

There is some truth to this. The substantive provisions criminalizing torture are basically the same as in the McCain bill, and I could live with them. It is the restriction on processes that could effectively hold the executive branch to these provisions that is worrisome. Restrictions on habeus were part of the McCain-Graham bill anyway -- this just ties it that much tighter.

From an international perspective, the compromise will almost certainly be acceptable to America's allies. They don't want Congress explicitly legalzing behaviour prohibited by the Common Article 3, but they aren't going to be fussed about blocking court review. I expect there is a bit of a sigh of relief among the OECD diplomatic types.

On the other hand, the American courts may be fussed. We will see how the inevitable constitutional challenges work out.

Thursday, September 21, 2006

Basquing in Diversity

The Pithlord's ancestry, to the best of his knowledge anyway, is pretty much all from the British isles. In addition to the fact that this makes him pale when he avoids the sun (as he should) and red with peeling skin when he doesn't, it provides for an extreme lack of coolness. Some among my co-ethnics attempted to solve this problem by alleging that they were "Celts" with mysterious Celtic Druidic ways. This was a problem when most of that Britishness was from England, though, and how cool can Celts be anyway?

But now it turns out, at least if Stephen Oppenheimer can be believed about such things, that the British, including the English, are not really Celtic or Anglo-Saxon (except narrowly on the male Y chromosone line), but are basically Basques. Seems some of the ancestral population of Europe headed over to Britain at the end of the last ice age, and then was wiped out of continental Europe except for the Basque country a millenium or two later.

If I am not much mistaken, those who think that the Neanderthals have continuing descendents have always put a lot of emphasis on the Basques. Which would make Brits an unusually Neanderthal bunch -- a proposition most of the world would accept without hesitation.

But now it turns out, at least if Stephen Oppenheimer can be believed about such things, that the British, including the English, are not really Celtic or Anglo-Saxon (except narrowly on the male Y chromosone line), but are basically Basques. Seems some of the ancestral population of Europe headed over to Britain at the end of the last ice age, and then was wiped out of continental Europe except for the Basque country a millenium or two later.

If I am not much mistaken, those who think that the Neanderthals have continuing descendents have always put a lot of emphasis on the Basques. Which would make Brits an unusually Neanderthal bunch -- a proposition most of the world would accept without hesitation.

Wednesday, September 20, 2006

How Does Rae Say Sorry?

If Rae becomes Liberal leader, how does he deal with that whole running-most-disastrous-postwar-Ontario-government thing?

I sympathize with the man. When the Pithlord was young and foolish, the Pithlord was young and foolish. It is only an accident of opportunity that I did not destroy all job growth in Canada's industrial heartland for five years, or wreck its public finances. I know I would have. Still, I was in my twenties and working on a philosophy degree, and he was the actual premier, and I have a blog and he wants to lead the country. So the question is a bit more urgent for the toothy one.

The easiest mistake to admit was to lose control of public sector spending. Rae already knows that this was a bad idea. The reasons for it -- high expectations from left-wing interest groups and public sector unions already dangerously coddled by Peterson and a fight with the Bank of Canada over aggregate demand which the provincial government could not win -- he could even talk about.

More difficult would be the sheer political correctness of the NDP regime. The most dangerous manifestation was the Employment Equity Act. It was impossible to follow. At least existing employees were grandfathered, which meant that Ontario companies could stay in compliance with the law only by not hiring anyone. Which is what they did. Harris just repealed the thing when he first met the legislature, leading right there to an employment boom. Pay Equity was almost as bad.

The Rae government had a commendable concern for the environment, combined with an uncommendable lack of pragmatism about how to fulfill its objectives. Rae is now interested in price mechanisms to reduce congestion and pollution, but these are politically tricky, of course.

Tony Blair's political life is about to end, but clearly he and Brown did discover something of a formula for progressive domestic policy. Rae knows this -- now he has to communicate it to the public.

Monday, September 18, 2006

Brave Political Prediction

Rae takes the Liberal leadership. There's an election in the first half of 2007. No one gets a majority.

(OK, the last one wasn't very brave...)

Update: The Rae prediction is a little less brave now, given the Globe poll which puts Iggy and Rae neck and neck among Liberals for first place, but with Rae in a comfortable lead as a second pick. How this translates into delegates is unknown, although I expect both Rae and Ignatieff will do better than the poll suggests in light of their greater ground strength.

(OK, the last one wasn't very brave...)

Update: The Rae prediction is a little less brave now, given the Globe poll which puts Iggy and Rae neck and neck among Liberals for first place, but with Rae in a comfortable lead as a second pick. How this translates into delegates is unknown, although I expect both Rae and Ignatieff will do better than the poll suggests in light of their greater ground strength.

The tribute Greek repression pays to Greek reason, and the story of Hannukah

One point that has been neglected in the discussion of the Pope's now notorious speech is his brief reference to the persecution of the Jews under the Hellenistic Seleucids and the cross-fertilization of Hellenistic and Jewish thought:

According to Maccabees I (which is part of the Greek Jewish bible, the Septuagiant, and then the Catholic Apocryphah), the Greek ruler of one of the successor kingdoms to the empire of Alexander the Great, Antiochus IV Epiphanes attempted to suppress the Jewish religion in the second century B.C. This inspired the revolt the successful revolt by the Maccabees and the establishment of a Jewish state. A miraculous version of these events is commemorated in Hannukah, which we goyim know about because the multicultural state used it as the first winter solstice celebration used to make the "Christmas season" more inclusive, notwithstanding its relative lack of importance in the Jewish tradition. (This kind of ecumenism is satirized by Jon Lovitz's Hannukah Harry, who constantly saves Christmas from evildoers).

I suspect that Benedict was trying to signal that the Greek tradition of respect for reason and dialectic did not always translate into practical tolerance. The norm of religious tolerance and rational persuasion dialectically derives from the Greek tradition - it did not at all times and in all places characterize it.

We all might have liked him to use some Christian examples, as well, but I think he was implying that the Inquisition or the Conquistadors were the successors of Antiochus, which is not a compliment.

Thus, despite the bitter conflict with those Hellenistic rulers who sought to accommodate it forcibly to the customs and idolatrous cult of the Greeks, biblical faith, in the Hellenistic period, encountered the best of Greek thought at a deep level, resulting in a mutual enrichment evident especially in the later wisdom literature.

According to Maccabees I (which is part of the Greek Jewish bible, the Septuagiant, and then the Catholic Apocryphah), the Greek ruler of one of the successor kingdoms to the empire of Alexander the Great, Antiochus IV Epiphanes attempted to suppress the Jewish religion in the second century B.C. This inspired the revolt the successful revolt by the Maccabees and the establishment of a Jewish state. A miraculous version of these events is commemorated in Hannukah, which we goyim know about because the multicultural state used it as the first winter solstice celebration used to make the "Christmas season" more inclusive, notwithstanding its relative lack of importance in the Jewish tradition. (This kind of ecumenism is satirized by Jon Lovitz's Hannukah Harry, who constantly saves Christmas from evildoers).

I suspect that Benedict was trying to signal that the Greek tradition of respect for reason and dialectic did not always translate into practical tolerance. The norm of religious tolerance and rational persuasion dialectically derives from the Greek tradition - it did not at all times and in all places characterize it.

We all might have liked him to use some Christian examples, as well, but I think he was implying that the Inquisition or the Conquistadors were the successors of Antiochus, which is not a compliment.

Sunday, September 17, 2006

A Challenge to the Legal Profession

Via Lindsay Beyerstein, take a look at this interview with Dr. Steven Miles, a bioethicist who has been immersing himself in the details of torture in Iraq and Guantanamo. Beyerstein points to Dr. Miles' point that beheadings against Western nationals began after the Abu Ghraib photos came out.

I want to take note of Dr. Miles' challenge to the legal profession:

Neither profession is likely to act soon. However, Bush is not going to be in power forever. This is definitely one to put in the calendar for 2015.

I want to take note of Dr. Miles' challenge to the legal profession:

A complaint for unprofessional conduct was filed with the California Medical Board against a Guantanamo physician. The Board refused to process the complaint. This kind of accountability is important. I get asked this question a lot by lawyers who, by the way have done nothing with regard to the lawyers who wrote the policy memoranda which led the U.S. to evade the Geneva conventions. When are the lawyers going to bring Yoo, Delahunty, Gonzales, et al., before the Bar to answer for their malfeasance?

Neither profession is likely to act soon. However, Bush is not going to be in power forever. This is definitely one to put in the calendar for 2015.

Sunday Morning Patriotism, Part Deux

If Canada had a soul (a dubious proposition, Moses thought) then it wasn't to be found in Batoche or the Plains of Abraham or Fort Walsh or Charlottetown or Parliament Hill, but in The Caboose and thousands of bars like it that knit the country together from Peggy's Cove, Nova Scotia to the far side of Vancouver Island. Signs over the ancient cash register reading NO CREDIT or TIP-PING ISN'T A CITY IN CHINA. A jar of rubbery pickled eggs floating in a murky brine, bags of Humpty Dumpty potato chips hanging on a spike. A moose head or buck's antlers mounted on the wall, the tractor caps hanging from it advertising GULF or JOHN DEERE or O'KEEFE ALE. The rip in the felt of the pool table mended with black tape. Toilet doors labelled BRAVES and SQUAWS or POINTERS and SETTERS. A Hi-Lo Double-Up JOKER POKER machine in one corner, a juke box in another, and the greasy sign over the kitchen door behind the bar reading EMPLOYEES ONLY BEYOND THIS POINT.

--Mordecai Richler, Solomon Gursky Was Here

Saturday, September 16, 2006

Vatican Distances Itself From Manuel II Paleologus

He's on his own on the whole Mohammed added nothing that was not evil or inhuman thing.

Friday, September 15, 2006

Left Conservatives, Red Tories, Doomed Traditions

All good things. Which is why you should read Russell Fox's meditation on them.

State Department Claims Rice's Relationship With Spawn-of-Elmer-McKay "Strictly Professional"

Well, they would, wouldn't they?

Jokes involving borrowed dogs, Belinda Stronach or Canadian foreign policy are invited in the comments.

Picture Credit CP PHOTO/Andrew Vaughan. Use of thumbnail to represent story believed to be fair use under Canadian and American copyright law.

Something We Should Be Bloody Afraid About

3 Quarks Daily makes fun of those of us "paranoid" enough to worry about high-energy physics experiments undoing reality as we know and like it. I don't see what's paranoid about it. If an experiment is worth doing it, that's because we don't yet really know how it will turn out. And if the wacky ideas of current cosmology, or something like them, are true, then they might well turn out very badly indeed.

Why we worry about Palestinian teenagers when we have lunatic string-theorists running about, I will never understand.

Why we worry about Palestinian teenagers when we have lunatic string-theorists running about, I will never understand.

An Ectomorph Questions the Rationale for Law School

Why have law schol (rather than the old-fashion articling with a few courses taught under the auspices of the law society), asks I Ectomorph. Other than the obvious conspiracy-in-restraint-of-trade angle?

I might be the wrong person to ask about this, since my practice is definitely atypical and since I liked law school more than I would like most practice of law.

I might be the wrong person to ask about this, since my practice is definitely atypical and since I liked law school more than I would like most practice of law.

Guest Blogging -- Creative Writing Fridays

The literatus has submitted a one-act musical on the subject of negotiated solutions in Afghanistan. In my view, it starts reasonably well, but the conclusion is a bit weak. Also, decapitation scenes are expensive to stage. But you can make up your own mind. You have to add the Oscar & Hammerstein-style score in your head.

MOTHER DIALOGUE

A strategy in one Act.

Cast.

Jack-Stephen Lewis-Layton, a promoter of virtue.

Mullah Omar, a suppressor of vice.

PithFella, a cunning strategist.

McKenzie McKandahar, an Afghan farmer.

Assorted Talibans and Princess Pats.

The Ghost of Edward Said.

Scene 1. The desert north of Waziristan. An enormous, polished round table of Canadian spruce dominates the sandy landscape, with empty chairs all around. PithFella knuckles his forehead in the lead chair. He sings.)

PithFella. Perhaps we're not so different, my friends.

We shoot and bomb each other, and call it deterrence.

Lewis-Layton says destroying you Talibs just makes ya madder.

Won't you come to the UN talks, and straighten out this matter?

Mullah Omar. Allahu Akbar! (Strikes PithFella in the head with an axe. Blood spurts. Pith collapses, Omar pauses.) (Beat.) Maybe we'd settle for just a province or two down here in the smack-producing regions. (Beat.) You'd be surprised, the Koran is down on chicks flaunting themselves, but it's very cool on heroin dealing. That's according to some of the more innovative imams, I mean.

Jack-Stephen Layton-Lewis. You patriarchal insensitive misogynist defender of indigenous cultural traditions! (Strikes Omar on the upper arm with a Concordia University calendar.) (Beat.) (J-S L-L begins massaging the neck of Omar, who glares.)

Talibans. Inshallah, asswipe! (They leap out of the wings and strike L-L in the head with an axe. Blood spurts. He collapses. They sing.)

Scene 2. Village battlegrounds south of Kandahar.

Talibans. We're just regular old Talibans,

Executing queers and whores, who wouldn't be a fan?

We wanna suppress any kinda quirk-a,

Put all the girls in their burkas;

We don't like vice, we're fond of virtue,

Hello Canadian boys, we're gonna shoot you.

Princess Pats. (Emerging.) But we admire your ethnic vibrancy.

Talibans. Well, around our land mines you'll find it chancy.

Princess Pats. Can't we build some roads and infrastructure?

Talibans. We're sickened by your female soldiers, fuckers.

Princess Pats. We'll bodycheck ya, then, instead of negotiation.

Talibs. You know we saw the Russians and Brits out of our nation.

Princess Pats. We're not invading this hot Labrador. We don't want it...

Thursday, September 14, 2006

Athens, Jerusalem and Mecca: Pope Says Interesting Things

Larison points to some fascinating pronouncements by the Bishop of Rome on the various projects of de-Hellenization of Christianity, and why they should be resisted. If there has ever been such a subtle scholarly intellect on St. Peter's throne, I am unaware of it.

Much to say about this. One objection is that the Pope's story of the dialogue between the Byzantine Emperor Manuel II Paleologus and a Persian interlocutor gives the impression that the tradition from Greek philosophy through medieval Christianity rejected coercion in religion (unlike Islam). The very learned Pope knows better. Leaving aside the specifically Greek Christian tradition (about which I know very little), Plato, Augustine and Aquinas all embraced religious coercion.

Andrew Sullivan wants to pull the Pope into the "civilizational conflict" between Islam and the West. And the Pope does indeed contrast Christianity's tie to a Greek conception of reason (presumptively persuasive) as opposed to Islam's emphasis on God's arbitrary will (presumptively violent). What Sullivan does not remark is how much Western Protestant-derived modernity owes to the Muslim idea of the primacy of will over reason, rather than Platonic-Patristic-Scholastic conception of the reasonableness of the universe. As Benedict hints, the key achievements of the Protestant West -- liberalism and the scientific method -- owe a lot to the dominant trend in medieval Muslim thought.

There are a number of ways of going at this, but I will try meta-ethics. In the Euthyphro, Socrates asks whether an act is pious because the gods command it, or the gods command it because it is pious. Plato's conclusion is that the gods could not make an act good just by commanding it -- rather, because they are benevolent, they command us to do what is good. In other words, the Good can be rationally understood and is prior to the will of personal deities. God cannot help but command what is moral.

At its more metaphysical, Platonism and neo-Platonism emphasized that ordinary human goods "participate" somehow in the Eternal Good and human reason can thereby imperfectly, but in some genuine sense, can understand the Divine. People like Rodney Stark emphasize this rationalization of the cosmos as a source of the scientific worldview.

The dominant trend in Islam rejected this way of thinking. God's power is emphasized so strongly that the idea that God could be bound by some rational good is rejected. What is good is good because God orders it so.

The line goes from medieval Islamic thought through the British nominalist scholastics to Hume and reason being the slave of the passions. Benedict makes this connection:

The rejection of the specifically Greek idea that irrationality was contrary to the divine nature in Islamic thought replays itself in Protestantism and then in the Enlightenment. But, contary to Stark, it is this "irrationalism" which is central to the scientific worldview. Scientific reason purports to be value-neutral -- you can obliterate Hiroshima or electrify Africa with the same technology. Similarly, liberalism reasons about law while being neutral about uses of the will. The will itself is not the subject of reason. So the specifically modern developments arise out of the Muslim rejection or the rationalist content of Greek thought on the grounds that it improperly limited God's freedom and power, a rejection that was influential outside of Islam. (Sola scriptura is also a very Muslim approach to the Christian scriptures.)

Benedict is aware of this, says this. Scientific materialism, liberalism and Islam are all aspects of the same ultimate heresy to him. At the same time, Benedict things he can affirm what is good about these things within the Catholic system because he does not divorce reason from faith or will.

But Benedict's reference to "a living historical Word" raises new issues. If it is impossible and undesirable to strip the Christian message of its Greek inculturation, it follows that the inculturation, the historical process, is part of the Christian truth. As are episodes in Jewish history, like the Babylonian exile, which in Benedict's narrative plays a crucial role in universalizing and making more profound the Jewish conception of their God. But if these historical episodes, these inculturations are part of the story of revelation, why cannot further inculturations be? The end of Benedict's speech shows an oddly Europe-specific vision for a universal Church.

Update: Apparently, Muslim activists have responded to Benedict's speech linking Islam with religious coercion (correctly, of course) by burning him in effigy. So that's all sorted then.

Update 2: Larison, who I trust on this, says there was relatively little religious coercion in the Byzantine Empire, with a few exceptions:

But other than that, the Byzantines seem to be better, from a modern religious liberal point-of-view, then either the Latin West or contemporary Islam.

Much to say about this. One objection is that the Pope's story of the dialogue between the Byzantine Emperor Manuel II Paleologus and a Persian interlocutor gives the impression that the tradition from Greek philosophy through medieval Christianity rejected coercion in religion (unlike Islam). The very learned Pope knows better. Leaving aside the specifically Greek Christian tradition (about which I know very little), Plato, Augustine and Aquinas all embraced religious coercion.

Andrew Sullivan wants to pull the Pope into the "civilizational conflict" between Islam and the West. And the Pope does indeed contrast Christianity's tie to a Greek conception of reason (presumptively persuasive) as opposed to Islam's emphasis on God's arbitrary will (presumptively violent). What Sullivan does not remark is how much Western Protestant-derived modernity owes to the Muslim idea of the primacy of will over reason, rather than Platonic-Patristic-Scholastic conception of the reasonableness of the universe. As Benedict hints, the key achievements of the Protestant West -- liberalism and the scientific method -- owe a lot to the dominant trend in medieval Muslim thought.

There are a number of ways of going at this, but I will try meta-ethics. In the Euthyphro, Socrates asks whether an act is pious because the gods command it, or the gods command it because it is pious. Plato's conclusion is that the gods could not make an act good just by commanding it -- rather, because they are benevolent, they command us to do what is good. In other words, the Good can be rationally understood and is prior to the will of personal deities. God cannot help but command what is moral.

At its more metaphysical, Platonism and neo-Platonism emphasized that ordinary human goods "participate" somehow in the Eternal Good and human reason can thereby imperfectly, but in some genuine sense, can understand the Divine. People like Rodney Stark emphasize this rationalization of the cosmos as a source of the scientific worldview.

The dominant trend in Islam rejected this way of thinking. God's power is emphasized so strongly that the idea that God could be bound by some rational good is rejected. What is good is good because God orders it so.

The line goes from medieval Islamic thought through the British nominalist scholastics to Hume and reason being the slave of the passions. Benedict makes this connection:

In contrast with the so-called intellectualism of Augustine and Thomas, there arose with Duns Scotus a voluntarism which ultimately led to the claim that we can only know God's "voluntas ordinata." Beyond this is the realm of God's freedom, in virtue of which he could have done the opposite of everything he has actually done.

This gives rise to positions which clearly approach those of Ibn Hazn and might even lead to the image of a capricious God, who is not even bound to truth and goodness. God's transcendence and otherness are so exalted that our reason, our sense of the true and good, are no longer an authentic mirror of God, whose deepest possibilities remain eternally unattainable and hidden behind his actual decisions.

[...]

Looking at the tradition of scholastic theology, the Reformers thought they were confronted with a faith system totally conditioned by philosophy, that is to say an articulation of the faith based on an alien system of thought. As a result, faith no longer appeared as a living historical Word but as one element of an overarching philosophical system.

The principle of "sola scriptura," on the other hand, sought faith in its pure, primordial form, as originally found in the biblical Word. Metaphysics appeared as a premise derived from another source, from which faith had to be liberated in order to become once more fully itself. When Kant stated that he needed to set thinking aside in order to make room for faith, he carried this program forward with a radicalism that the Reformers could never have foreseen. He thus anchored faith exclusively in practical reason, denying it access to reality as a whole.

The rejection of the specifically Greek idea that irrationality was contrary to the divine nature in Islamic thought replays itself in Protestantism and then in the Enlightenment. But, contary to Stark, it is this "irrationalism" which is central to the scientific worldview. Scientific reason purports to be value-neutral -- you can obliterate Hiroshima or electrify Africa with the same technology. Similarly, liberalism reasons about law while being neutral about uses of the will. The will itself is not the subject of reason. So the specifically modern developments arise out of the Muslim rejection or the rationalist content of Greek thought on the grounds that it improperly limited God's freedom and power, a rejection that was influential outside of Islam. (Sola scriptura is also a very Muslim approach to the Christian scriptures.)

Benedict is aware of this, says this. Scientific materialism, liberalism and Islam are all aspects of the same ultimate heresy to him. At the same time, Benedict things he can affirm what is good about these things within the Catholic system because he does not divorce reason from faith or will.

But Benedict's reference to "a living historical Word" raises new issues. If it is impossible and undesirable to strip the Christian message of its Greek inculturation, it follows that the inculturation, the historical process, is part of the Christian truth. As are episodes in Jewish history, like the Babylonian exile, which in Benedict's narrative plays a crucial role in universalizing and making more profound the Jewish conception of their God. But if these historical episodes, these inculturations are part of the story of revelation, why cannot further inculturations be? The end of Benedict's speech shows an oddly Europe-specific vision for a universal Church.

Update: Apparently, Muslim activists have responded to Benedict's speech linking Islam with religious coercion (correctly, of course) by burning him in effigy. So that's all sorted then.

Update 2: Larison, who I trust on this, says there was relatively little religious coercion in the Byzantine Empire, with a few exceptions:

There are exceptional cases: the forcible conversion of Jews and violent repression of monophysites under Heraclius; the persecution of the Montanists under Leo III; executions of a few Paulicians and Athinganoi under Michael I; executions of some Bogomils under Alexios I. There were inter-confessional persecutions, most of which took the form of sending people into exile or deposing them from their sees. It might be of interest to note that one of the worst periods of violent persecution in these internal church disputes was under Michael VIII, who sought to enforce church union with Rome.

But other than that, the Byzantines seem to be better, from a modern religious liberal point-of-view, then either the Latin West or contemporary Islam.

Professor Rice Lectures Us on Insensitive and Hurtful Talk of Negotiation

These are people who whipped women in stadiums given to them by the international community to play soccer, who refused to let women learn to read. The Taliban made Afghanistan a failed state and a terrorist haven for Al-Qa'ida so that they could launch the Sept. 11 attack. What's to negotiate?

Negotiation is not a reward for being good. Negotiation is communication with an opponent in a non-zero-sum game for the purposes of getting a better result than you could get without negotiation. We negotiated with Stalin. In fact, Karazai has previously attempted negotiation with parts of the Taliban.

The US did not rule negotiation out in principle in Vietnam. Even the Soviets didn't in Afghanistan between 1979 and 1988. Even in the best case scenario, we are going to want to get some of the elements fighting us in Afghanistan invested in a negotiated, political solution.

The worst part of this is the condescending way Professor Rice talks to us. Our soldiers are dying in a war of immese strategic interest to her country and she talks to us like slow children.

Something (other than "staying the course") needs to be done in Afghanistan. At this point, recognizing that the war in Afghanistan, unlike the one in Iraq, had a genuine strategic rationale, I would prefer more troops combined with a political strategy. But, sooner or later, the Canadian public is going to turn to withdrawal. Rice probably bumped those numbers up a few points.

Tuesday, September 12, 2006

Let Us Now Praise the Unknown Indian Mathematical Genius Who Generated the Concept of the Zero Magnitude

Because that concept comes in very handy when estimating the likelihood that Stephen Harper is going to give a speech like David Cameron just gave.

It's a politician's speech, so you can't expect great clarity of analysis. But the "billboard paragraph" is clear enough:

In a sense, talk of "friendship" in international politics is dubious. States cannot be friends -- they are instrumentalities of coercion, sometimes justified coercion, but coercion. But if we have to engage in this cant, we should at least acknowledge that a friend is not someone who defers to your judgment and power, but a person with whom you have a relationship of reciprocal loyalty.

Cameron sensibly excludes democratization, but not the prevention of genocide, from the possible justifications for war. He also specifically criticizes Guanatamo Bay, which the Bush administration is unlikely to forgive. The peroration invokes Gladstone, which is a bit odd for a Tory leader, and a bit frustrating for those of us who share Disraeli's opinion of Gladstone's romanticism, if not Disraeli's own imperial ambitions.

In any event, Cameron has pointed to how a genuinely conservative Anglophone leader should regard America and the world. It is certainly a great improvement over the degraded Asperite bellowing that passes for right-wing thought in this country.

It's a politician's speech, so you can't expect great clarity of analysis. But the "billboard paragraph" is clear enough:

We should be solid but not slavish in our friendship with America.

It all comes down to a sense of confidence.

Your long-standing friend will tell you the truth, confident that the friendship will survive.

In a sense, talk of "friendship" in international politics is dubious. States cannot be friends -- they are instrumentalities of coercion, sometimes justified coercion, but coercion. But if we have to engage in this cant, we should at least acknowledge that a friend is not someone who defers to your judgment and power, but a person with whom you have a relationship of reciprocal loyalty.

Cameron sensibly excludes democratization, but not the prevention of genocide, from the possible justifications for war. He also specifically criticizes Guanatamo Bay, which the Bush administration is unlikely to forgive. The peroration invokes Gladstone, which is a bit odd for a Tory leader, and a bit frustrating for those of us who share Disraeli's opinion of Gladstone's romanticism, if not Disraeli's own imperial ambitions.

In any event, Cameron has pointed to how a genuinely conservative Anglophone leader should regard America and the world. It is certainly a great improvement over the degraded Asperite bellowing that passes for right-wing thought in this country.

Choices

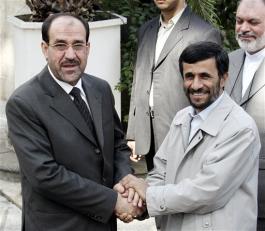

This picture of the Prime Minister and President of Iraq and Iran(via Yglesias) doesn't resolve any of the dilemmas America finds itself in. But what it should do, at minimum, is put an end to this stupid conception of a monolithic "Islamofascism" that is just like the Comintern in 1936.

The dilemma in the Middle East is that the opposition to the old tyrannies (and reasonable monarchies like Jordan) is not led by Bohemian playwrights and trade union leaders like Havel or Walesa, but by totalitarian religious fanatics. Basically, you have two options: you can back the status quo come hell or high water, or you can back off and see what happens if more popular regimes come to power. Neither is without pain or risk.

What you can't do is proclaim, "Long live democracy! But no Islamists!" Because democracy means Islamists.

Technical Announcement

Haloscan commenting and trackback have been added to this blog.

Typekey authentication doesn't exist yet, so I'm going to moderate comments. The downside is that yours may not show up until I get around to moderating. But the alternative isn't pretty...

Update: I seem to have lost all the existing comments in the transition. I suspect this was human error on my part. Apologies!

More Optimistic Update: A technically-skilled person on the Haloscan discussion board tells me that the old comments aren't gone, but are just hidden. Another such person has provided code that may allow the Pith & Substance technical staff to fix this problem.

I must say that experiencing the generosity of nerds leavens my austere Augustinian view of post-lapsarian human nature.

Another Update: Well, it involved a lot of manual work, but I got the old comments into Haloscan back to the beginning of July. I took the opportunity to attribute the comments that are clearly the work of the Literatus to him. There are a small number of comments, mostly from MSS, before then, which I will someday get around to Haloscanning.

Final Update: I realize that I used the phrase "manual work" to refer to highlighting with a mouse, copying and pasting. I need to get outside.

Typekey authentication doesn't exist yet, so I'm going to moderate comments. The downside is that yours may not show up until I get around to moderating. But the alternative isn't pretty...

Update: I seem to have lost all the existing comments in the transition. I suspect this was human error on my part. Apologies!

More Optimistic Update: A technically-skilled person on the Haloscan discussion board tells me that the old comments aren't gone, but are just hidden. Another such person has provided code that may allow the Pith & Substance technical staff to fix this problem.

I must say that experiencing the generosity of nerds leavens my austere Augustinian view of post-lapsarian human nature.

Another Update: Well, it involved a lot of manual work, but I got the old comments into Haloscan back to the beginning of July. I took the opportunity to attribute the comments that are clearly the work of the Literatus to him. There are a small number of comments, mostly from MSS, before then, which I will someday get around to Haloscanning.

Final Update: I realize that I used the phrase "manual work" to refer to highlighting with a mouse, copying and pasting. I need to get outside.

Monday, September 11, 2006

Case Comment -- The Queen v. Kong -- Thumbs Down

On a February night in 2002 at 3 am outside a Calgary nightclub, Vuthy Kong and some of his friends got into a fight with Peter Miu and some of his friends. Kong had a knife. Miu died the next morning of a stab wound in the left side of his abdomen. He was cut once in the front severing his intestine, and once in the back trying to escape. Miu was 5'5" and had scoliosis and asthma.

Kong said he only waved his knife in a horizontal fashion several feet away from Miu. His lawyer implied that another member of Kong's gang actually made the cuts.

At trial, Kong's main defence was that someone else stabbed Miu. But "in the alternative", if Kong did stab Miu his lawyer said it was in self-defence. The trial judge didn't think much of the self-defence argument, and wouldn't let it go to the jury. The jury decided that Kong was the stabber and convicted him of manslaughter.

The legal issue now before the Supreme Court of Canada was whether the self-defence theory had an "air of reality", such that the trial judge should have let the jury consider it as a possible reason for acquittal. Obviously, a jury system requires that there be some leeway for juries to hear unlikely factual arguments before a conviction can be allowed.

The majority of the Alberta Court of Appeal didn't think Kong's alternative defence passed the laugh test. The fatal cut was a punching blow while stepping forward into Miu. Kong claimed his only knife move was a slash in the air feet away from the victim. Justice Wittman dissented at the appellate level, but never explains how a defensive slashing of the air while moving back could possibly be consistent with the evidence of the autopsy.

The Supreme Court of Canada unanimously preferred Justice Wittman's dissent, but doesn't say why. They ordered a new trial.

The practice of allowing appeals without providing reasons is a rare one. It may have occurred here because the appeal is as of right. It is obviously important for trial judge's to be very careful about taking any defence away from an accused: the jury system is imperfect, but it's the system we have got. At the same time, there has to be a minimal amount of consistency in a self-defence plea. It is unfortunate (and a measure of bad form) that the SCC didn't at least comment on why they were willing to overrule the lower courts.

Update: Alex's post on this case is here.

Kong said he only waved his knife in a horizontal fashion several feet away from Miu. His lawyer implied that another member of Kong's gang actually made the cuts.

At trial, Kong's main defence was that someone else stabbed Miu. But "in the alternative", if Kong did stab Miu his lawyer said it was in self-defence. The trial judge didn't think much of the self-defence argument, and wouldn't let it go to the jury. The jury decided that Kong was the stabber and convicted him of manslaughter.

The legal issue now before the Supreme Court of Canada was whether the self-defence theory had an "air of reality", such that the trial judge should have let the jury consider it as a possible reason for acquittal. Obviously, a jury system requires that there be some leeway for juries to hear unlikely factual arguments before a conviction can be allowed.

The majority of the Alberta Court of Appeal didn't think Kong's alternative defence passed the laugh test. The fatal cut was a punching blow while stepping forward into Miu. Kong claimed his only knife move was a slash in the air feet away from the victim. Justice Wittman dissented at the appellate level, but never explains how a defensive slashing of the air while moving back could possibly be consistent with the evidence of the autopsy.

The Supreme Court of Canada unanimously preferred Justice Wittman's dissent, but doesn't say why. They ordered a new trial.

The practice of allowing appeals without providing reasons is a rare one. It may have occurred here because the appeal is as of right. It is obviously important for trial judge's to be very careful about taking any defence away from an accused: the jury system is imperfect, but it's the system we have got. At the same time, there has to be a minimal amount of consistency in a self-defence plea. It is unfortunate (and a measure of bad form) that the SCC didn't at least comment on why they were willing to overrule the lower courts.

Case Comment of R. v. Kong, 2006 SCC 40

Update: Alex's post on this case is here.

Rhetorical Choices: The "War" on Terror and Revolution from Above

The fifth anniversary of the attacks is an obvious, almost inevitable, hook for a blog post. Pushed by fred s., I want to talk about the key political/strategic/legal question arising from the attacks: is the conflict that al Qaeda unleashed that sunny New York day a "war" or a crime-suppression effort?

I didn't always think this question was important. Back in 2001-2002, the "war" talk seemed to me to be basically a way of reaffirming how seriously America and its allies were taking the conflict. Anyway, there clearly was a need to make war against the Taliban to deprive al Qaeda of its state sponsor. Those who argued that we needed to deal with bin Laden and his minions as criminals struck me as partly right, but not sufficiently serious about the scope of the conflict. It was only after the Axis-of-Evil speech and the Bush administration position on the extra-legal status of Guantanamo bay that I realized that the war/crime distinction was an important one after all.

In general, those with state power tend to want to deny the status of war opponent to those without it. The British state called the Provos criminals; the Provos were the ones who insisted they were warriors. The official of the regime referring to revolutionaries as "bandits" is a figure of cliché.

There are obvious strategic reasons for this. A criminal is just an anti-social menace. An enemy army, on the other hand, is presumptively legitimate. You can make a treaty with an enemy army, but only a plea bargain with a criminal.

So there was something slightly odd about the Bush administration's immediate preference for a "war" model. You would think that the status quo superpower would be highly reluctant to dignify a ragtag group of murderous religious fanatics with the distinction previously held by the mighty USSR. After all, the West at the time was very reluctant to promote the Bolsheviks from a group of bandits and adventurers temporarily in control of Petrograd to a state enemy.

There seem to have been two rationales for this choice. The first arises out of the common law criminal justice system, as augmented by the Warren court. There would be some understandable reluctance to let99 al Qaeda go free rather than incarcerate one innocent person, as recommended by Blackstone. But could not an alternative, less procedurally robust criminal law system be devised? That seems to be where the US will finally go now. Most legal systems have had special procedures for insurrectionaries and terrorists.

Another appealing idea was to mobilize the people -- something democracies tend to do in those wars that are not mere colonial skirmishes. Operationally, Afghanistan and Iraq *have* been colonial skirmishes, and the idea of mobilizing the population conflicted with the greater imperative of keeping the economy on track. The result was a system of passive mobilization -- orange alerts, etc. I wouldn't go so far as to say that this was always a purely political fraud. But there was a contradiction at the heart of it. In reality, Islamic terrorism (without nuclear weapons) is a relatively minor problem -- the risk cannot be eliminated altogether, but when a small portion of the resources at the command of the American state are mobilized against it, the point of diminishing returns is quickly reached. The cost of genuine mobilization would be staggering, and the benefits small.

But even though the rational response was pretty limited, something had to be done that was commensurate with the shock of the original attack.

The program seized upon -- social revolution of the Islamic world from without and from above -- could be considered big enough, since even the resources of the United States cannot possibly accomplish it. It seems odd in two ways:

First, because it is hard to understand why the status quo power wants to make radical transformations. I have no answer to this dilemma, although it does seem that, in general in human history, 'revolutions from above' are more common than those from below. If you have power, you want to accomplish things with it.

Second, the objectives of the revolution were contradictory: simultaneously to make the Islamic world more bourgeois while making the West less so. It was not just a matter of making the Islamic world "democratic" (a word that is less about a system of majority rule and more about a civilization of risk-minimization and economic growth).

Those who called for this revolution wanted to bring some of the hard, masculine virtues they saw in the attackers to the people (especially, the men) that were the products of democracy. From Fukuyama, we learn that they really feared the "last man", the final, perfect product of the risk society. They wanted to toughen him up. But they wanted to do it by selling him on perfect security and by somehow transforming the Muslim fanatic into the post-modern consumer.

So where are we now? No one really still believes that the revolution-from-above will work. America, as a world power, will soon have to turn its attention to how it minimizes its losses. The forward momentum of liberalism from 1989 will be slowed, maybe reversed. On the other hand, Islamism has no prospect of being itself a world power, the way that Communism did. The technology of mass death gets cheaper, better and more accessible every year. I suspect that nuclear non-proliferation is dead, and will be accepted as such by everybody by 2010. The logic of war becoming more dangerous but less likely will probably continue until the unlikely happens.

The best we can do is plug away, case by case, at building legal institutions. And criticizing the ones we've got, of course.

I didn't always think this question was important. Back in 2001-2002, the "war" talk seemed to me to be basically a way of reaffirming how seriously America and its allies were taking the conflict. Anyway, there clearly was a need to make war against the Taliban to deprive al Qaeda of its state sponsor. Those who argued that we needed to deal with bin Laden and his minions as criminals struck me as partly right, but not sufficiently serious about the scope of the conflict. It was only after the Axis-of-Evil speech and the Bush administration position on the extra-legal status of Guantanamo bay that I realized that the war/crime distinction was an important one after all.

In general, those with state power tend to want to deny the status of war opponent to those without it. The British state called the Provos criminals; the Provos were the ones who insisted they were warriors. The official of the regime referring to revolutionaries as "bandits" is a figure of cliché.

There are obvious strategic reasons for this. A criminal is just an anti-social menace. An enemy army, on the other hand, is presumptively legitimate. You can make a treaty with an enemy army, but only a plea bargain with a criminal.

So there was something slightly odd about the Bush administration's immediate preference for a "war" model. You would think that the status quo superpower would be highly reluctant to dignify a ragtag group of murderous religious fanatics with the distinction previously held by the mighty USSR. After all, the West at the time was very reluctant to promote the Bolsheviks from a group of bandits and adventurers temporarily in control of Petrograd to a state enemy.

There seem to have been two rationales for this choice. The first arises out of the common law criminal justice system, as augmented by the Warren court. There would be some understandable reluctance to let

Another appealing idea was to mobilize the people -- something democracies tend to do in those wars that are not mere colonial skirmishes. Operationally, Afghanistan and Iraq *have* been colonial skirmishes, and the idea of mobilizing the population conflicted with the greater imperative of keeping the economy on track. The result was a system of passive mobilization -- orange alerts, etc. I wouldn't go so far as to say that this was always a purely political fraud. But there was a contradiction at the heart of it. In reality, Islamic terrorism (without nuclear weapons) is a relatively minor problem -- the risk cannot be eliminated altogether, but when a small portion of the resources at the command of the American state are mobilized against it, the point of diminishing returns is quickly reached. The cost of genuine mobilization would be staggering, and the benefits small.

But even though the rational response was pretty limited, something had to be done that was commensurate with the shock of the original attack.

The program seized upon -- social revolution of the Islamic world from without and from above -- could be considered big enough, since even the resources of the United States cannot possibly accomplish it. It seems odd in two ways:

First, because it is hard to understand why the status quo power wants to make radical transformations. I have no answer to this dilemma, although it does seem that, in general in human history, 'revolutions from above' are more common than those from below. If you have power, you want to accomplish things with it.

Second, the objectives of the revolution were contradictory: simultaneously to make the Islamic world more bourgeois while making the West less so. It was not just a matter of making the Islamic world "democratic" (a word that is less about a system of majority rule and more about a civilization of risk-minimization and economic growth).

Those who called for this revolution wanted to bring some of the hard, masculine virtues they saw in the attackers to the people (especially, the men) that were the products of democracy. From Fukuyama, we learn that they really feared the "last man", the final, perfect product of the risk society. They wanted to toughen him up. But they wanted to do it by selling him on perfect security and by somehow transforming the Muslim fanatic into the post-modern consumer.