My initial intention with this blog was to comment on obscure legal arcana. So I'm pleased on a number of levels that the Supreme Court of Canada in December released its decision in R. v. Henry.

In the broader public sphere, there is a lot of talk about judicial activism, and excessive judicial power. I think the last election shows that the public is worried about too much power in the hands of judges, despite the overwhelming support Canadians have for the Charter.

Not suprisingly, there is relatively little talk about the ways the legal process can confine the power of judges. The issues are a bit technical for a general audience, and the legal profession is highly invested in expanding judicial power. But a number of traditional process doctrines about standing, pleadings, evidence and the scope of appellate review helped confine what judges could do.

The problem is that the contours of these doctrines are in the hands of the judiciary itself. That isn't to say that every judge in every case wanted to expand the scope of judicial power: it is easy to come up with counter-examples. But the pressure on the judicial system to take over more and more of social life has been pretty relentless since the 1970s, and there is still relatively little in the way of organized counter-pressure.

Anyway, one of the powerful constraints on judicial power, particularly the power of final appellate bodies, was the old distinction between the holding (ratio decedendi) and the comments (obiter dicta) in the case. The holding consists of the minimum necessary norms to decide the issue between the parties, while the dicta are all the other things a judge may be minded to say.

Traditionally, just because the majority of a court said something didn't make it law. Only the holding/ratio was binding on future judges. Although this sounds incredibly boring and technical, along with standing rules, and being confined to pleadings and evidence, it held judicial tyranny at bay. A majority of judges (or their clerks) couldn't make a proposition the law just by saying it -- it had to be necessary to decide a real case between real people. It also fit with what we know about the cognitive structure of normative intuition -- people are much better at knowing what should be done in a particular case then in theorizing why.

The holding/obiter distinction was apparently buried in R. v. Sellars, [1980] 1 SCR 527. The headnote said that lower courts now had to follow anything higher courts said. This was just before the Charter era began, and soon we had an orgy of undigested political theory and advocacy-based "legal scholarship" in Supreme Court of Canada judgments.

The good news is that Henry has revived the distinction. I'll get to the bad news in another post.

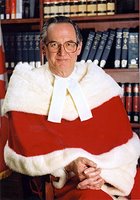

Picture of Mr. Justice Binnie from Supreme Court of Canada collection. Credit Phillipe Landreville

No comments:

Post a Comment