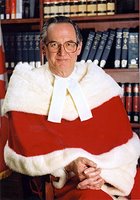

At the most obvious level, he's going to try to lead my party. That means I'm going to have to read some of his stuff.

As to the speech, it starts with the obligatory praise of the land, with examples chosen carefully from each time zone, and then segues into the archetypical immigrant experience of Tsarist nobility marrying into the Ontarian haute bourgeoisie. [/unfair and hypocritical snark]

Overall, I liked the domestic part of the speech, but the international stuff makes me nervous.

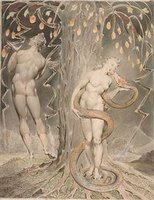

The most problematic theme is the one Ignatieff starts with: "ask not what you can do for your country; ask what your country can do for the world." It is especially troubling from Ignatieff. As a journalist/professor, his theme was always that the "West" should use its infinite power to rescue everyone from the consequences of the conflicts endemic to the human condition. He ignored completely the limits of the "West's" power, limits that Canada faces in spades. His lack of sympathy for particularism led him to ignore what armies, and military force, are made from.

Ignatieff shows a lot of finesse on Quebec. He is dead right that the real asymmetry that needs to be conceded is an asymmetry of sentiment. Quebec will mean something to Quebecois that Ontario will never mean to Ontarians, whether or not the Quebec government has any powers that the Ontario government does not.

There are a few false notes. He talks about Quebec being part of the Canadian solution "from the Quiet Revolution onwards." The implicit denigration of traditional Quebec is gratting. In fact, Quebec needs to rethink some of the legacies of the Quiet Revolution, particularly the way it created an interlocking state-labour-capital anti-competitive elite, and there is some evidence that it is starting to do so. The embarrassment a single generation had for Quebec prior to 1962 should not deprive an entire people of its heritage.

And then there is the obligatory reference to Quebec not assenting to the constitutional deal in 1981, although each individual part of that deal turns out to be as popular in Quebec as anywhere else. Iggy is well-placed to point out that we expect the Tutsis and Hutus to "get over" a massive genocide in 1994, so harping on the non-unanimous resolution of a many-year constitutional negotiation a generation ago is just demeaning.

Ignatieff emphasizes exactly the right things on the role of the federal government, and he has made some progress over traditional Liberal dogma just by recognizing that that role is a limited one.

[The federal government] is charged with the defense of the country, the protection of its borders , the development of national infrastructure and a national economic market, as well as safeguarding the rights of citizenship. That all Canadians hold in common. Without respect for these federal domains, we cannot have a country.

A common border, a common market and a common citizenship.

The common border is a crucial one, and the harder-headed American milieu may make Ignatieff improve on traditional Liberalism here.

Personally, I don't think direct federal regulation of securities, for example, is necessary. But there should be federal laws requiring each provincial security regulator to respect the certification provided by the others (and similar laws for professional qualifications, pensions, etc., etc.) We can have the benefits of regulatory competition and inter-operability.

He makes good sense on equalization. It needs to be simplified, and it needs to be based on population.

Rhetorically, I think it is wrong to equate the situation of aboriginal Canadians, and the mutual obligations we need to work through, with the issues facing voluntary "visible minority" immigrants.

Finally, I don't think you can overestimate the importance of experience. Ignatieff is obviously a talented, charismatic guy, but there is still some dues-paying that has to be done.

Update:Red Tory defends Ignatieff from the charge of being more ex-pat than man.