Modern law is big on disclosure of information, particularly government information. But there are exceptions -- no exception more important (to lawyers) than communications between a lawyer and her client. Documents created in the course of this communication are subject to solicitor-client privilege.

The boundaries of privilege are set by law, and therefore the sort of thing you can argue in front of a judge about. But there is an inherent problem with arguing about whether a document should remain secret. If the lawyer challenging the purported privilege can see it, then it isn't secret anymore. But if she can't see it, then it's pretty hard to argue about. Instead, we end up with something of an inquisitorial system, in which judges themselves read the documents and decide without the benefit of meaningful argument.

The world is an imperfect place, and there is no ideal way of resolving this dilemma. But one judge of the Ontario Divisional Court came up with what looked like an elegant solution. If the person challenging the privilege is willing to (a) have her lawyer look at the documents under a commitment of confidentiality and (b) agree not to use the lawyer except for the argument about the documents, then it looks like most of the interests involved are (imperfectly) addressed.

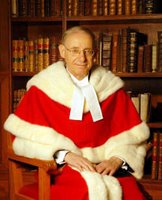

Today, the Supreme Court, in a judgment authored by the new boy, Marshall Rothstein, said "no" to this solution. Rothstein said that limits on solicitor-client privilege (unlike lesser reasons to keep documents secret) require a showing of "absolute necessity." This looks to the Pithlord like one of the many forms of cost-benefit analysis that courts engage in, but with the thumb placed very firmly indeed on the side of lawyers' secrets.

I don't object to solicitor-client privilege, or to making it difficult to get around. But I object to "absolute necessity" tests, especially for common law rules. Sure, solicitor-client privilege is important. But "informer privilege" (that is-- your right, if you tell the police about what the Hell's Angels have been up to, not to have that revealed to them) strikes me as EVEN MORE IMPORTANT, and doesn't get this kind of judicial solicitude.

In the end, I think the lower court's compromise was sensible, and the SCC had no business overturning it.

The big issue of this term -- whether the Feds can, in deportation proceedings of non-citizens and non-permanent residents, keep information they have as to why somebody is a danger to Canada -- is similar in structure, and the reasons for secrecy are more compelling than for most solicitor-client relationships. It will be interesting to see how the SCC respond.

Case Comment of Goodis v. Ontario (Ministry of Correctional Services), 2006 SCC 31

Picture of the Honourable Mr. Justice Marshall Rothstein from Supreme Court of Canada collection. Photo credit: Philippe Landreville

Update: Simon Chester of SLAW blogs about Goodis here.

No comments:

Post a Comment