On Friday, the SCC

ruled 4-3 that a non-money judgment by a US federal court should not automatically be enforced in Ontario. The Pithlord gives the majority decision in

Pro Swing Inc. v. Elta Golf Inc., 2006 SCC 52 the "thumbs up", but that really means I think it is the lesser evil compared to the Chief Justice's dissent. I see no reason that to depart from the long-established rule that only final money judgments of foreign courts should be enforced domestically, as all seven justices did. Blather about "globalization" is not a reason. And, in any event, even if we accept that globalization has changed the policy calculus here, it ought to be up to the legislatures, not the courts, to enact this kind of law reform.

Two things can happen when you win a civil lawsuit: you can be awarded a sum of money ("liquidated damages") or you can get some qualitative order telling the other party it has to do a bunch of stuff. Historically, the common law courts only gave awards of damages. This led the courts of equity to try to increase their market share by providing qulitative remedies -- injunctions, accountings, declarations of trust and other goodies.

Because qualitative judgments are trickier to administer and more intrusive, the courts of equity always retained large amounts of discretion about how and when to grant these remedies. The common law courts purported to provide more clear-cut justice. The combination of discretion and qualitative remedies made the Courts of Equity rather procedurally convoluted places: it is not for nothing that

Bleak House satirizes the Courts of Chancery.

Globalization is actually a very old story, and the English courts long ago recognized that if a halfway honest foreign court found that A owed B a certain sum of money, then A should generally be allowed to enforce that judgment in England without having to prove A's case all over again. But there was a lot of suspicion of qualitative judgments in other countries. The question of when they would be available would differ, they might be unjust and the common law courts thought such things were for those bozos in Chancery anyway.

In the Pithlord's respectful view, this distinction was always a good one. To this day, qualitative remedies are exceptional in common law jurisdictions. Whether to extend such things is an important part of sovereignty. If ABC Ltd. entered into a transaction in some foreign spot, and ended up owing XYZ Inc. a sum of dinars, then we can normally say that said sum is owing everywhere, including here, and other courts usually take the same view. But telling people what they can and cannot do if they want to avoid jail is a different thing.

Pro Swing was a trademark case (the underlying sin of the defendant was to market its golf clubs under a name that could be confused with Pro Swing's clubs). Trademark law involves a difficult trade off between allowing companies to retain investments in their brand with free speech and free commerce. One policy decision is whether to permit judicial silencing of brand invaders or only to allow compensation. It should be recognized that the silencing remedy has a much greater potential impact on free expression. At minimum, each jurisdiction must decide for itself when and whether to allow judicial silencing as a response.

When it came to light that Elta Golf was marketing dubiously-named golf clubs on the Internet, Pro Swing and Elta Golf agreed to a consent order, which was entered in a federal court in Ohio. (It is worth noting that nothing in the order suggests it was intended to have application outside the United States.) Elta apparently violated the consent order, and Pro Swing was awarded a civil contempt order -- which included injunctions and the requirement of an accounting (Elta had to provide evidence of its profits, and hand the money over to Pro Swing, but a specific sum was not yet determined). Elta is based in Toronto, and that is presumably where most of its records are kept.

On a traditional view of the law, Pro Swing would have to invoke Ontario's civil rules to obtain letters rogatory to get the info it needed to quantify the wrongfully-obtained profits. Only the Federal Court could give Pro Swing an injunction in Canada, and only for violation of

Canada's trademark legislation. Once there was a judgment in Yankee dollars, then Ontario courts would help Pro Swing enforce, but that would be it. Contempt orders could not possibly be applied cross-border.

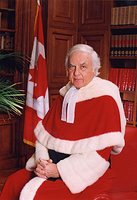

The result from the majority judgment is in keeping with traditional law. Unfortunately, Justice Deschamps' "on the one hand" does not always let her "on the other hand" know what it is doing. This means the law will be unsettled, and someone with clearer ideas will ultimately have to sort it out.

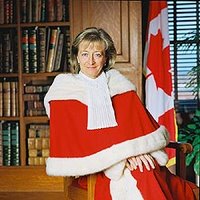

The Chief Justice's decision shows greater clarity of thought, but it would basically allow the application of qualitative orders from foreign jurisdictions apply here, unless the same narrow tests that apply to money judgments are met.

There are a couple annoying things about the Chief Justice's decision. First, she refers to Law Reform Commission recommendations (which, I understand, are actually limited to inter-provincial application of qualitative judgments) as reasons for judges to change the law. On the contrary, if an issue is the subject of potential legislative reform, and the legislatures have not acted, that suggests there are policy reasons

not to act, and the whole thing should be left with the political process. McLachlin's discussion here reminds me of how she used class action legislation in some provinces to

force class actions on the provinces that had deliberately refrained from enacting them.

The other annoying thing is the assertion that constitutional values of privacy (and, in this case, freedom of speech) don't matter in civil actions, since the coerced disclosure is to sworn private enemies, rather than the state. It strikes me that this makes things worse, not better. I might be worried about what some bureaucrat will do with my personal information, but I can probably rely on the reality that he or she will probably be more interested in coffee breaks and Solitaire. Giving my personal information to profit-maximizing corporations, particularly ones I have a dispute with, is more problematic, and should only happen when there has been a clear legislative judgment to require me to do it.

Finally, it is extremely odd that both justices take the principle of "comity" as the dominant one in private international law, but fail to give any weight to the fact that American courts would never domestically enforce a non-money judgment of a Canadian court.

Anyway, the private international law revolution stalled a bit on Friday, which is good, but will probably be temporary relief.

Case Comment of Pro Swing Inc. v. Elta Golf Inc.

Photo of Madam Justice Deschamps credited to Phillipe Landreville, Supreme Court of Canada collection

Update: An ectomorphic take on

Pro Swing can be found

here. Andy makes the point that the civil law judges voted against bringing the common law into line with their own.