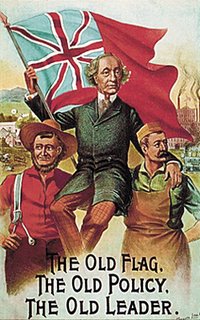

As you might have guessed from this post, I have been reading Donald Creighton's biography of John A. Macdonald, and I've decided I quite like him (Macdonald, not Creighton). Personally, Macdonald was an attractive combination of humour, hard work, loyalty to family (including to a very sick first wife and a hydrocephalic daughter) and mild alcoholism. Politically, he was the ideal progressive conservative, combining a firm loyalty to his own with a sympathetic openness to the other, rejecting equally the bigoted right and the doctrinaire left.

Throughout his career, Macdonald was initially suspicious of the great reforms and projects he ended up accomplishing -- from the abolition of the church reserves and seigneurial system when he was a young man to the federal union of British North America and the acquisition of the West at the climax of his life. In each case he was cautious about the wisdom of the idea before he took it on, but was tenacious and pragmatic once he was convinced it was necessary.

Throughout Macdonald's career, racial and religious divisions between French Catholics and Anglo-Scottish Protestants dominated everything. "Liberal" and "radical" politicians -- from Durham to Brown -- deliberately inflamed these divisions. Macdonald was a Tory Presbyterian, and had no hesitation about his loyalties -- he was willing to take firm action, including hanging Riel after his last rebellion. He was a happy partisan. But he was above all hostile to polarization and "principled" demagogy. The mark Macdonald left in the politics of this country still maddens heirs of Brown like Andrew Coyne, who prefer Trudeau's governing by a combination of machismo and abstraction. Dangerous men, the Coynes and Browns.

It's a bit silly to pretend that the Presbyterian bourgeois Victorian lawyer was a throne-and-altar CONSERVATIVE, or that the Tories of his era created some fundamentally anti-modern anti-liberal trend in Canadian society. Macdonald had a lawyer's respect for conservatism of form. He knew that the development of half a continent could best be promoted by secure property and free contract. He was a protectionist, although on other occasions he hoped for comprehensive free trade with the US. I don't suppose he ever imagined human nature was perfectible, or that ethnic antagonism could be eliminated, as opposed to managed. He thought education should be Christian, although he wanted each sect, even Papists, to educate its own children as they wished.

There have been periodic attempts to turn Macdonaldism into a uniquely Canadian ideology. Protectionists are particularly inclined to do this with the National Policy. It makes little sense, since what he stood for -- a pragmatic respect for tradition, combined with an openness to necessary change -- mean different things in different eras. Unlike ideology, they do not acquit us from having to think the issues of our own day over again. As a supporter of provincial autonomy, I am pleased that his constitutional vision was ultimately modified by the struggles of his articling student, Oliver Mowat, and the Judicial Committee. The British tie could never have been retained in the form Macdonald understood it. But all in all, we were lucky in our founding father.

No comments:

Post a Comment