The Pithlord is delighted to announce that he will have new parental responsibilities in the very near future.

Great news, but it means changes around here.

In order to avoid contributing to Canada's burgeoning divorce rate, I'm going to put the blog on hold for a little while.

I'm not going to post at all until at least the New Year. After that, I will see what level of posting I can reasonably keep up.

I appreciate all the support and links, particularly from Matthew Shugart, Scott Lemieux, Daniel Larison and Andy the Ectomorph (a diverse bunch!). Thanks also to Phillipe Landreville, Supreme Court of Canada portrait photographer, for most of the site's visual content.

Google Ad revenues are in the high one figures!

Friday, December 08, 2006

Thursday, December 07, 2006

Why should he sell your wheat?

Dion is going to bring back the Wheat Board monopoly if and to the extent the Tories undermine it.

One annoying thing about this debate is the presumption that only producers have a legitimate stake in it. Not all wheat is exported, and higher prices for staples is pretty regressive.

It's probably good politics for Dion, though. Liberal support among wheat farmers is zero plus or minus 4% nineteen times out of twenty. However support for the monopoly lines up, getting those votes is still an improvement for the Libs on the status quo.

Wednesday, December 06, 2006

You Can't Say That on Pith & Substance

OK, for the first time, I decided to censor a comment. We have a bit of a free-wheeling discussion here about race, ethnicity and culture -- all hot button issues. I felt a comment went over the line, but I guess that compels me to try to state better where the line is.

The accusation of "racism" or "anti-Semitism" has frequently been used to prevent discussion of things Candians need to discuss. At the same time, taboos exist for a reason and on a private site, even the strongest libertarian would accept I can enforce what I think are necessary taboos.

I am willing to hear arguments that some cultures have strengths and weaknesses that others do not. It is possible that various genetically-based traits are differently distributed among different human populations. Not all religions can be true.

However, I expect people not to engage in setting up their own ethnic group as morally and intrinsically superior to everyone else. I am not going to listen to tales of collective guilt. Ethnic slurs (and other incivilities) are verboten.

As I have previously indicated, this site is not a democracy and there is no right of appeal.

The accusation of "racism" or "anti-Semitism" has frequently been used to prevent discussion of things Candians need to discuss. At the same time, taboos exist for a reason and on a private site, even the strongest libertarian would accept I can enforce what I think are necessary taboos.

I am willing to hear arguments that some cultures have strengths and weaknesses that others do not. It is possible that various genetically-based traits are differently distributed among different human populations. Not all religions can be true.

However, I expect people not to engage in setting up their own ethnic group as morally and intrinsically superior to everyone else. I am not going to listen to tales of collective guilt. Ethnic slurs (and other incivilities) are verboten.

As I have previously indicated, this site is not a democracy and there is no right of appeal.

Tuesday, December 05, 2006

Hindsight, Part II

Fred S. reminds me of this unprescient statement by a certain pseudonymous Canadian lawyer:

Oops. Still two (as yet) unfalsified predictions in that post.

Well, the purpose of bringing in a francophone has generally been to win francophone votes. Since Dion is more unpopular in Quebec than either Rae or Ignatieff, I don't think he is going to get it. I think he's the sentimental favourite, but sentimental favourites don't win.

Oops. Still two (as yet) unfalsified predictions in that post.

Dion Won't Give Up Dual Citizenship

A bit late, the Toronto Star reports that Dion is a dual French/Canadian citizen, and intends to stay that way.

This actually might change my vote. The citizenship relationship ought to be a big deal. The Canadian government has an obligation to protect Canadian citizens, and I think Canadian citizens have correlative obligations of loyalty to the Canadian state. Same with French citizens to the French state (and the French are more serious about this than we are.) Since you can't have dual loyalties, we shouldn't permit dual citizenship.

It's bad enough that we have so many dual citizens in the ordinary population. To have one of them seek to be Prime Minister is too much.

Update: Andy suggests handing Dion over to the French authorities for treason against the Fifth Republic.

This actually might change my vote. The citizenship relationship ought to be a big deal. The Canadian government has an obligation to protect Canadian citizens, and I think Canadian citizens have correlative obligations of loyalty to the Canadian state. Same with French citizens to the French state (and the French are more serious about this than we are.) Since you can't have dual loyalties, we shouldn't permit dual citizenship.

It's bad enough that we have so many dual citizens in the ordinary population. To have one of them seek to be Prime Minister is too much.

Update: Andy suggests handing Dion over to the French authorities for treason against the Fifth Republic.

Monday, December 04, 2006

Hindsight

Andy inspires me to a familiar argument:

My first complaint is about the parenthetical to the subjunctive concession. Whatever the epistemic benefits of hindsight, they are unnecessary for the conclusion that there exists at least one possible world in which the benefit/cost ratio of the invasion of Iraq, net of opportunity costs, is less than unity. What we know now, we could have known then.

The Pithlord wasted a good deal of time in '02-'03 arguing with Iraq War supporters, so everything about that era -- its music, its fashions and its bar debates -- remains impressed on my memory. Two things stand out in particular:

1. Everybody in the whole world (except the Anglophone centre and right) predicted disaster, more-or-less of the kind that occurred. Hippies did. Gaullists did. Andean peasants, Buchananite reactionaries, John Paul II, Al Gore, the career US military, pulp novelists, realist IR professors and pissy arts students all saw this one coming. I know it's kind of embarrassing for the English-speaking right to admit that they didn't have the foreign policy chops of the Berkeley Women Studies' department, but them's the facts.

2. When one argued with Anglophone righties back in the day, one could almost see them twitch with anticipation of being proven right against all of the persons mentioned in point #1 above. Their narratives of Churchill and Reagan were not really attempts to understand the present in light of the past, but the sweet anticipation of being a vindicated minority (albeit one in possession of the world's only military superpower). If Afghanistan's #1 problem right now was a sense of bourgeois ennui, I can't imagine them taking well to talk of "hindsight being 20/20." No, they would demand nothing less than acknowlegment that History had proven them right.

OK, on to less petty points. Andy's claim is that (a) demography is (if present trends continue) going to deal enormous power to the Islamic world that it currently doesn't have, and therefore (b) it is worth taking risks now so that they will be boring pacifists in fifty years.

Point (a) is impossible to refute altogether. But I doubt that we will see an Islamic ascendancy. If you want to worry about civilizational challenges to the West, I'd still bet on China. Having lots of people -- divided by country, confession and ethnicity -- is not power in the contemporary world.

True, you don't need to be a rival civilization to explode a nuclear device in a major Western city. But you don't need a demographic boom to do that either.

Moderate, prosperous and democratic Islamic societies would be nice. Domesticating Islam -- making it more liberal and bourgeois (which, for now, conflicts with making it more democratic) -- is a good thing. But conservatives are supposed to be the people who ask not whether a project is well-intentioned, but whether it will work. Reducing poverty among the working poor is a good thing -- but the minimum wage might not be. Best alternative technology standards for auto emissions may have negative effects if they price out new cars. Could it be possible that ill-thought out attempts to "democratize" a culture North Americans see no reason to try to learn the first thing about could have even worse effects?

To the extent anyone can make anyone else more bourgeois, it is by doing business with them. If we occupy and militarize, then we give power to precisely the undemocratic, extremists forces of anti-prosperity.

Those were just arguments three years ago. Now they are experience.

As for our reputation for the future, every power in the world suffers defeats. Better to suffer smaller ones than bigger ones, so it is better to cut losses now than later. We should fulfill our commitments in Afghanistan. The US should make sure that the Kurds' security is guranteed (it has no other real allies in Iraq). But we should get clarity about what we are fighting for, and what we are not.

Update: Here is a September 2002 paid announcement in the New York Times setting out the realist case against the war. The key bullet point is, "Even if we win easily, we have no plausible exit strategy. Iraq is a deeply divided society that the United States would have to occupy and police for many years to create a viable state."

If you're wondering why we're in Afghanistan or why we (Canadians) should be in Iraq, it is more than anything because we need to counter the notion that all this is feeding on...that the West will risk nothing in defence of its supposed "ideals". Even if one were to concede (in hindsight) that the Iraq invasion wasn't the best thing to do in 2003, it is crucial not to give up now. The establishment, there and in Afghanistan, of moderate, prosperous and democratic Islamic societies is still possible, and one of our last best hopes for a "sustainable" world.

My first complaint is about the parenthetical to the subjunctive concession. Whatever the epistemic benefits of hindsight, they are unnecessary for the conclusion that there exists at least one possible world in which the benefit/cost ratio of the invasion of Iraq, net of opportunity costs, is less than unity. What we know now, we could have known then.

The Pithlord wasted a good deal of time in '02-'03 arguing with Iraq War supporters, so everything about that era -- its music, its fashions and its bar debates -- remains impressed on my memory. Two things stand out in particular:

1. Everybody in the whole world (except the Anglophone centre and right) predicted disaster, more-or-less of the kind that occurred. Hippies did. Gaullists did. Andean peasants, Buchananite reactionaries, John Paul II, Al Gore, the career US military, pulp novelists, realist IR professors and pissy arts students all saw this one coming. I know it's kind of embarrassing for the English-speaking right to admit that they didn't have the foreign policy chops of the Berkeley Women Studies' department, but them's the facts.

2. When one argued with Anglophone righties back in the day, one could almost see them twitch with anticipation of being proven right against all of the persons mentioned in point #1 above. Their narratives of Churchill and Reagan were not really attempts to understand the present in light of the past, but the sweet anticipation of being a vindicated minority (albeit one in possession of the world's only military superpower). If Afghanistan's #1 problem right now was a sense of bourgeois ennui, I can't imagine them taking well to talk of "hindsight being 20/20." No, they would demand nothing less than acknowlegment that History had proven them right.

OK, on to less petty points. Andy's claim is that (a) demography is (if present trends continue) going to deal enormous power to the Islamic world that it currently doesn't have, and therefore (b) it is worth taking risks now so that they will be boring pacifists in fifty years.

Point (a) is impossible to refute altogether. But I doubt that we will see an Islamic ascendancy. If you want to worry about civilizational challenges to the West, I'd still bet on China. Having lots of people -- divided by country, confession and ethnicity -- is not power in the contemporary world.

True, you don't need to be a rival civilization to explode a nuclear device in a major Western city. But you don't need a demographic boom to do that either.

Moderate, prosperous and democratic Islamic societies would be nice. Domesticating Islam -- making it more liberal and bourgeois (which, for now, conflicts with making it more democratic) -- is a good thing. But conservatives are supposed to be the people who ask not whether a project is well-intentioned, but whether it will work. Reducing poverty among the working poor is a good thing -- but the minimum wage might not be. Best alternative technology standards for auto emissions may have negative effects if they price out new cars. Could it be possible that ill-thought out attempts to "democratize" a culture North Americans see no reason to try to learn the first thing about could have even worse effects?

To the extent anyone can make anyone else more bourgeois, it is by doing business with them. If we occupy and militarize, then we give power to precisely the undemocratic, extremists forces of anti-prosperity.

Those were just arguments three years ago. Now they are experience.

As for our reputation for the future, every power in the world suffers defeats. Better to suffer smaller ones than bigger ones, so it is better to cut losses now than later. We should fulfill our commitments in Afghanistan. The US should make sure that the Kurds' security is guranteed (it has no other real allies in Iraq). But we should get clarity about what we are fighting for, and what we are not.

Update: Here is a September 2002 paid announcement in the New York Times setting out the realist case against the war. The key bullet point is, "Even if we win easily, we have no plausible exit strategy. Iraq is a deeply divided society that the United States would have to occupy and police for many years to create a viable state."

Best Federal Program Ever -- Axed

BKN opines:

I'm a bit of a law-and-order type myself, and I think populist complaints of an erratic and overly-lenient sentencing system are vindicated by sound empirical work. But I have to raise an objection to the cancellation of a program giving federal inmates free tatoos. Personally, I can't think of a better investment of public money than providing some easy feature for shaky prosectuion visual ID witnesses.

Seriously though, I'm provisionally impressed by the fact that Dion, unlike his fellow policy-wonk counterpart on the other side of the aisle, seems to believe (as I do) that the state has functions beyond spewing jeep exhaust at brown-skinned foreigners and devising ways to wring a few more drops of vengeance from convicts.

I'm a bit of a law-and-order type myself, and I think populist complaints of an erratic and overly-lenient sentencing system are vindicated by sound empirical work. But I have to raise an objection to the cancellation of a program giving federal inmates free tatoos. Personally, I can't think of a better investment of public money than providing some easy feature for shaky prosectuion visual ID witnesses.

Dion -- Things Could Definitely Be Worse

I am nervous about parties that pick a candidate because he doesn't have the negatives of two more plausible candidates. No doubt the Alberta Tories will survive such things, but the federal Liberals have to exist in a multi-party democracy. We know Dion is a political science professor, has a thin skin, makes Stephen Harper seem like a man of the people, is hard to understand in English and has taken positions that annoy the majority of francophones.

But he got this far. And he has a history of being right (unlike Rae or Ignatieff). I am cautiously optimistic, which is the only kind of optimistic anyone should ever be.

But he got this far. And he has a history of being right (unlike Rae or Ignatieff). I am cautiously optimistic, which is the only kind of optimistic anyone should ever be.

Saturday, December 02, 2006

None of these teams can win

My slightly unfair précis of John Ibbitson's reaction to the Liberal leadership campaign's first ballot results. Somehow, though, somebody has to win.

Note that the calculation of the total number of votes required to win is off. The Liberal Party of Canada can't seem to divide by two. Maybe they are subtly trying to set up an Adscam defence -- no corruption, just bad math skills!

Note that the calculation of the total number of votes required to win is off. The Liberal Party of Canada can't seem to divide by two. Maybe they are subtly trying to set up an Adscam defence -- no corruption, just bad math skills!

Friday, December 01, 2006

Thursday, November 30, 2006

2004: When Iggy was young and foolish, Iggy was young and foolish

Antiwar.com reminds us of this charming quote from Michael Ignatieff in 2004:

Or as Trotsky put it,

Vegetarians, Kantians, priests and Quakers are advised to vote for Rae or Dion.

To defeat evil, we may have to traffic in evils: indefinite detention of suspects, coercive interrogations, targeted assassinations, even pre-emptive war.

Or as Trotsky put it,

As for us, we were never concerned with the Kantian-priestly and vegetarian-Quaker prattle about the 'sacredness of human life.'

Vegetarians, Kantians, priests and Quakers are advised to vote for Rae or Dion.

My kind of redneck

Jim Webb. Bush's lucky Webb didn't wrestle him to the ground.

Update: I sort of meant this as a joke, but via Daniel McCarthy, I see that a source for The Hill is saying Webb actually confessed to a desire to "slug" the Commander in Chief. All I can say is I admire that man's anger management skills.

Update: Scott McConnell has an interesting article about Webb in The American Conservative.

Update: I sort of meant this as a joke, but via Daniel McCarthy, I see that a source for The Hill is saying Webb actually confessed to a desire to "slug" the Commander in Chief. All I can say is I admire that man's anger management skills.

Update: Scott McConnell has an interesting article about Webb in The American Conservative.

Daniel Davies: Why Investing in a Reputation as an Idiot Isn't Worth It

Basically, because after you have committed moral crimes, killed or injured your soldiers and blown billions of dollars, all you have is a reputation as an idiot.

Here. (Warning: Game Theory)

Here. (Warning: Game Theory)

Wednesday, November 29, 2006

The Revenge of the 401 Refugee

In response to Jim Henley's thoughtful post, I reminisce about a visit by Amy Chua, author of World on Fire, to the U. of Toronto law school back in the day:

It would be too bad if the trip down the 401 leads to a completely deracinated liberalism.

I remember Amy Chua (before she was famous) giving her lecture on market-dominant minorities and populist backlash at the University of Toronto law school. She didn’t mention Quebec, and during the question period, she disclaimed any knowledge. It didn’t matter — the effect of her speech was absolutely electric.

What you have to realize is that a huge part of English Canada’s elite are Hwy 401 refugees. Exiled in their own country. Je me souviens aussi.

It would be too bad if the trip down the 401 leads to a completely deracinated liberalism.

Tuesday, November 28, 2006

The Other Shoe: Recognizing Anglos as a nation within a united Canada

Read Andy the Ectomorph on the next step in our dialectic. If the Québécois are a nation, and Acadians are a nation, and the Métis are a nation and (of course), the First Nations are nations, then what does that make the remainder? A nation!

That's fine with me. I don't cry for the loss of Andrew Coyne's dream state. I don't want the homogeneous (although supposedly diverse), post-national liberal "civic nationalist" polity which there are only individuals and governments. (And by governments, he means the Federal government, with the judiciary at the apex.) Yuck.

The trouble is not with the Québécois (OK, there are troubles there -- an overweening state, an excessive reaction to a Catholic past, but the point is, those are NOT OUR TROUBLES). The trouble is us, our inability to reestablish an identity when the British Empire passed away, other than the identity of consumers and rights holders.

Update: You should read "gabriel"'s thoughts on the Commons resolution. There's a good discussion starting in response to Reihan Salaam's post at the American Scene.

Late Night Update After Finishing Very Technical Legal Submission: I realize there are deeper objections to Coyne's worldview, but I do sort of wonder at the idea that recognizing obviously true things constitutes suicide. Water is wet, Ottawa is cold in December, poutine's bad for the arteries, the Pope's Catholic and bears defecate in the woods. If the Qu´eb´ecois aren't a nation, who is?

Further Update: It is probably silly to link to someone a lot more famous than oneself, but I like Cosh's take. On Pith & Substance, of course, every day is Dominion Day.

That's fine with me. I don't cry for the loss of Andrew Coyne's dream state. I don't want the homogeneous (although supposedly diverse), post-national liberal "civic nationalist" polity which there are only individuals and governments. (And by governments, he means the Federal government, with the judiciary at the apex.) Yuck.

The trouble is not with the Québécois (OK, there are troubles there -- an overweening state, an excessive reaction to a Catholic past, but the point is, those are NOT OUR TROUBLES). The trouble is us, our inability to reestablish an identity when the British Empire passed away, other than the identity of consumers and rights holders.

Update: You should read "gabriel"'s thoughts on the Commons resolution. There's a good discussion starting in response to Reihan Salaam's post at the American Scene.

Late Night Update After Finishing Very Technical Legal Submission: I realize there are deeper objections to Coyne's worldview, but I do sort of wonder at the idea that recognizing obviously true things constitutes suicide. Water is wet, Ottawa is cold in December, poutine's bad for the arteries, the Pope's Catholic and bears defecate in the woods. If the Qu´eb´ecois aren't a nation, who is?

Further Update: It is probably silly to link to someone a lot more famous than oneself, but I like Cosh's take. On Pith & Substance, of course, every day is Dominion Day.

Sunday, November 26, 2006

Democratic Imperialism: Once again on why it is a bad idea

I know many of you like to see bloody-minded arguifying. The Pithlord has been busy for personal and work reasons, but the Pithlord understands. So I point you to a fight I get into with ex-pat philosopher "Akrasia" on the subject of whether Canada's foreign policy should involve "democracy promotion".

Labels:

Afghanistan,

Canada,

human rights,

imperialism,

Iraq,

realism

Asymmetrical Thoughts on Quebec and the Constitution, Part I

Let's suppose there was a change X to the Constitution that a plurality of English Canadians disliked intensely, but would prefer to secession. And let's suppose that the median resident of Quebec would oppose secession if X became part of the Constitution, but not otherwise. Will X get enacted?

No. Secession will happen or the status quo, but not X.

But why? Wouldn't it be the most efficient result? What about Ronald Coase?

There are many reasons, all of them I suppose subsumable under the term "transaction costs". Too many veto points is one answer. But another is that the implicit deal "Enact X and we won't separate" is unenforceable. The ROC could agree to X, and Quebec could still have another referndum in a few years.

ROCkers may be unfashionable, but they are not stupid. So, X is not going to happen.

The only possible way out of this is if Quebec would agree, in exchange for X, to an explicit supermajority requirement for an independence referendum in the constitution. If the Constitution said, "A province may leave Canada, if, and only if, 2/3 of the electors in a province-wide referendum vote 'Yes' to the question, "Should [your province] leave Canada and become an independent state?", then I bet you could get ROCkers to agree to a lot in exchange.

The thing is that there is no X such that Quebec would give up the ability to leave on a 50% plus one vote in exchange. It doesn't exist. So it is secession or the status quo.

No. Secession will happen or the status quo, but not X.

But why? Wouldn't it be the most efficient result? What about Ronald Coase?

There are many reasons, all of them I suppose subsumable under the term "transaction costs". Too many veto points is one answer. But another is that the implicit deal "Enact X and we won't separate" is unenforceable. The ROC could agree to X, and Quebec could still have another referndum in a few years.

ROCkers may be unfashionable, but they are not stupid. So, X is not going to happen.

The only possible way out of this is if Quebec would agree, in exchange for X, to an explicit supermajority requirement for an independence referendum in the constitution. If the Constitution said, "A province may leave Canada, if, and only if, 2/3 of the electors in a province-wide referendum vote 'Yes' to the question, "Should [your province] leave Canada and become an independent state?", then I bet you could get ROCkers to agree to a lot in exchange.

The thing is that there is no X such that Quebec would give up the ability to leave on a 50% plus one vote in exchange. It doesn't exist. So it is secession or the status quo.

Thursday, November 23, 2006

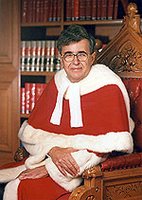

R. v. Déry

The Supreme Court of Canada ruled today that you can't attempt to conspire to commit a crime. It takes more work than that.

Apparently, the accused in this case thought about stealing some booze, discussed it with another member of the lumpenproletariat, but never actually got to the point of agreeing on a positive course of action. Everyone's been at meetings like that.

Justice Fish noted that no one has ever been convicted of attempting to conspire before, and didn't see any reason to start now.

From a crime control perspective, the major downside with this case will likely be the free pass it gives persons who think they are conspiring with a confederate who is in fact in the employ of Her Majesty. Parliament might want to fix that one.

Case Comment of R. v. Déry, 2006 SCC 53

Resolved: This Blog recognizes that the Québécois form a nation within a united Canada

When I heard that Harper was going to introduce a motion recognizing "Quebec" (for so it was reported on CBC Radio news last night) as a nation, I have to admit my first reaction was about the politics of it. "Why would Harper want to save Iggy's political bacon like this?" But bigger issues are in play.

Whether the motion is true depends, of course, on what you mean by the "Québécois" and by "a nation". I have no trouble recognizing that the descendents of the habitants represent an ethnic nation, or, as we used to say, a "race".

However, this nation is not coincident with the residents of the province of Quebec. It is a majority in Quebec, and nowhere else, but that isn't the same thing.

If we give in to history, and call this nation/race the Québécois, then the resolution is true. I would even be happy to go further and say that one of the reasons we insist on strong provinces is so that the one jurisdiction in which this nation is the majority has the power it needs to ensure the future of this nation/race.

Trudeau objected to this, because Trudeau was a principled liberal. He didn't think states should be in the business of ensuring futures to nations/races. I admire the way Trudeau insisted on his principles, but I don't share them. Whatever the later excesses of their nationalisms, I am pleased the Canadian Indians and the "Queébécois" told him to buzz off. I am less pleased that my people bought Truedau's principles as a way of fighting separatism. In the end, redrawing the borders of your country is a better thing than teaching your children to be embarrassed at their own identity.

Update: Andrew Coyne has an entire aviary in opposition to the Commons motion recognizing the Québécois as a nation.

Whether the motion is true depends, of course, on what you mean by the "Québécois" and by "a nation". I have no trouble recognizing that the descendents of the habitants represent an ethnic nation, or, as we used to say, a "race".

However, this nation is not coincident with the residents of the province of Quebec. It is a majority in Quebec, and nowhere else, but that isn't the same thing.

If we give in to history, and call this nation/race the Québécois, then the resolution is true. I would even be happy to go further and say that one of the reasons we insist on strong provinces is so that the one jurisdiction in which this nation is the majority has the power it needs to ensure the future of this nation/race.

Trudeau objected to this, because Trudeau was a principled liberal. He didn't think states should be in the business of ensuring futures to nations/races. I admire the way Trudeau insisted on his principles, but I don't share them. Whatever the later excesses of their nationalisms, I am pleased the Canadian Indians and the "Queébécois" told him to buzz off. I am less pleased that my people bought Truedau's principles as a way of fighting separatism. In the end, redrawing the borders of your country is a better thing than teaching your children to be embarrassed at their own identity.

Update: Andrew Coyne has an entire aviary in opposition to the Commons motion recognizing the Québécois as a nation.

Tuesday, November 21, 2006

Bad Style and Bad Law

Via Larry Solum's excellent Legal Theory Blog, I found Paul Horwitz's 2000 article in the Osgood Hall Law Review entitled, "Law's Expression: The Promise and Perils of Judicial Opinion Writing in Canadian Constitutional Law".

Horwitz's argument is that the style of judical writing makes a difference for the quality of law, particularly constitutional law. The typical judicial "opinion" (note to PH: in Canada, they are referred to as "reasons for judgment") takes an omniscient and dogmatic tone, states the obvious and irrelvant at length and sets out lots of "tests" and "hurdles" that rarely do much of the work of deciding the case. Horwitz not only thinks that this style is boring, but that it is also bad for the law, and although he doesn't make much of a case for his position, I tend to agree.

Instead, Horwitz would like to see a style of "open-textured minimalism." The Pithlord likes the minimalism part, but to the extent I understand what "open-textured" means (Socrates meets Solon, I suppose), I doubt that most judges are really up to the task. Judges are successful lawyers who have avoided creating powerful enemies-- intelligent and hard-working, usually, but not prophets. A few of them -- like Oliver Wendell Holmes or Richard Posner -- have original minds, but even these people are only acceptable as judges to the extetnt they suppress their most original ideas when on the bench.

Horwitz doesn't care for the Oakes test, and presumably would decry the Delgamuukw decision in which Lamer goes on and on at Russian novel length setting out impractical and many-stage tests, while never deciding any issue actually between the parties. So far, the Pithlord can add little more than "Amen" and "Hallelujah".

The Pithlord gets crankier when Horwitz reveals what he thinks of as skookum judicializing. Horwitz is a big fan of the Secession Reference, in which the Court held that Quebec couldn't unilaterally separate, but that a "clear majority on a clear question" would trigger a duty to negotiate the terms of secession. By Lamer-era standards, the decision is a model of clarity and pith. And the underlying political tradeoff is defensible. However, it seems to me that this case shows a bit of a weakness in the Horwitz approach, since the style cannot hide the substantive trickery of the decision. Our Constitution has a detailed set of provisions for its own amendment. Referenda, whether clear or opaque, have no role in those provisions. Legally, the question the Court was asked in 1997 wasn't hard at all: Quebec couldn't secede (except through revolution) unless at least the federal Parliament and six other provinces agreed, and there is no legal requirement for those other entities to consider a Quebec referendum at all.

Whatever its stylistic merits, then, the Secession Reference was lawless. That strikes me as the bigger point.

Technical note: The University of Montreal website with Supreme Court of Canada decisions seems a bit wacky right now, so I haven't tried to hyperlink the decisions referred to. I may get around to it someday.

Horwitz's argument is that the style of judical writing makes a difference for the quality of law, particularly constitutional law. The typical judicial "opinion" (note to PH: in Canada, they are referred to as "reasons for judgment") takes an omniscient and dogmatic tone, states the obvious and irrelvant at length and sets out lots of "tests" and "hurdles" that rarely do much of the work of deciding the case. Horwitz not only thinks that this style is boring, but that it is also bad for the law, and although he doesn't make much of a case for his position, I tend to agree.

Instead, Horwitz would like to see a style of "open-textured minimalism." The Pithlord likes the minimalism part, but to the extent I understand what "open-textured" means (Socrates meets Solon, I suppose), I doubt that most judges are really up to the task. Judges are successful lawyers who have avoided creating powerful enemies-- intelligent and hard-working, usually, but not prophets. A few of them -- like Oliver Wendell Holmes or Richard Posner -- have original minds, but even these people are only acceptable as judges to the extetnt they suppress their most original ideas when on the bench.

Horwitz doesn't care for the Oakes test, and presumably would decry the Delgamuukw decision in which Lamer goes on and on at Russian novel length setting out impractical and many-stage tests, while never deciding any issue actually between the parties. So far, the Pithlord can add little more than "Amen" and "Hallelujah".

The Pithlord gets crankier when Horwitz reveals what he thinks of as skookum judicializing. Horwitz is a big fan of the Secession Reference, in which the Court held that Quebec couldn't unilaterally separate, but that a "clear majority on a clear question" would trigger a duty to negotiate the terms of secession. By Lamer-era standards, the decision is a model of clarity and pith. And the underlying political tradeoff is defensible. However, it seems to me that this case shows a bit of a weakness in the Horwitz approach, since the style cannot hide the substantive trickery of the decision. Our Constitution has a detailed set of provisions for its own amendment. Referenda, whether clear or opaque, have no role in those provisions. Legally, the question the Court was asked in 1997 wasn't hard at all: Quebec couldn't secede (except through revolution) unless at least the federal Parliament and six other provinces agreed, and there is no legal requirement for those other entities to consider a Quebec referendum at all.

Whatever its stylistic merits, then, the Secession Reference was lawless. That strikes me as the bigger point.

Technical note: The University of Montreal website with Supreme Court of Canada decisions seems a bit wacky right now, so I haven't tried to hyperlink the decisions referred to. I may get around to it someday.

Monday, November 20, 2006

Pro Swing -- Thumbs Up

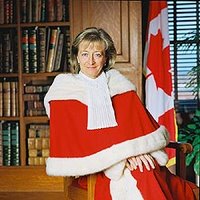

On Friday, the SCC ruled 4-3 that a non-money judgment by a US federal court should not automatically be enforced in Ontario. The Pithlord gives the majority decision in Pro Swing Inc. v. Elta Golf Inc., 2006 SCC 52 the "thumbs up", but that really means I think it is the lesser evil compared to the Chief Justice's dissent. I see no reason that to depart from the long-established rule that only final money judgments of foreign courts should be enforced domestically, as all seven justices did. Blather about "globalization" is not a reason. And, in any event, even if we accept that globalization has changed the policy calculus here, it ought to be up to the legislatures, not the courts, to enact this kind of law reform.

Two things can happen when you win a civil lawsuit: you can be awarded a sum of money ("liquidated damages") or you can get some qualitative order telling the other party it has to do a bunch of stuff. Historically, the common law courts only gave awards of damages. This led the courts of equity to try to increase their market share by providing qulitative remedies -- injunctions, accountings, declarations of trust and other goodies.

Because qualitative judgments are trickier to administer and more intrusive, the courts of equity always retained large amounts of discretion about how and when to grant these remedies. The common law courts purported to provide more clear-cut justice. The combination of discretion and qualitative remedies made the Courts of Equity rather procedurally convoluted places: it is not for nothing that Bleak House satirizes the Courts of Chancery.

Globalization is actually a very old story, and the English courts long ago recognized that if a halfway honest foreign court found that A owed B a certain sum of money, then A should generally be allowed to enforce that judgment in England without having to prove A's case all over again. But there was a lot of suspicion of qualitative judgments in other countries. The question of when they would be available would differ, they might be unjust and the common law courts thought such things were for those bozos in Chancery anyway.

In the Pithlord's respectful view, this distinction was always a good one. To this day, qualitative remedies are exceptional in common law jurisdictions. Whether to extend such things is an important part of sovereignty. If ABC Ltd. entered into a transaction in some foreign spot, and ended up owing XYZ Inc. a sum of dinars, then we can normally say that said sum is owing everywhere, including here, and other courts usually take the same view. But telling people what they can and cannot do if they want to avoid jail is a different thing.

Pro Swing was a trademark case (the underlying sin of the defendant was to market its golf clubs under a name that could be confused with Pro Swing's clubs). Trademark law involves a difficult trade off between allowing companies to retain investments in their brand with free speech and free commerce. One policy decision is whether to permit judicial silencing of brand invaders or only to allow compensation. It should be recognized that the silencing remedy has a much greater potential impact on free expression. At minimum, each jurisdiction must decide for itself when and whether to allow judicial silencing as a response.

When it came to light that Elta Golf was marketing dubiously-named golf clubs on the Internet, Pro Swing and Elta Golf agreed to a consent order, which was entered in a federal court in Ohio. (It is worth noting that nothing in the order suggests it was intended to have application outside the United States.) Elta apparently violated the consent order, and Pro Swing was awarded a civil contempt order -- which included injunctions and the requirement of an accounting (Elta had to provide evidence of its profits, and hand the money over to Pro Swing, but a specific sum was not yet determined). Elta is based in Toronto, and that is presumably where most of its records are kept.

On a traditional view of the law, Pro Swing would have to invoke Ontario's civil rules to obtain letters rogatory to get the info it needed to quantify the wrongfully-obtained profits. Only the Federal Court could give Pro Swing an injunction in Canada, and only for violation of Canada's trademark legislation. Once there was a judgment in Yankee dollars, then Ontario courts would help Pro Swing enforce, but that would be it. Contempt orders could not possibly be applied cross-border.

The result from the majority judgment is in keeping with traditional law. Unfortunately, Justice Deschamps' "on the one hand" does not always let her "on the other hand" know what it is doing. This means the law will be unsettled, and someone with clearer ideas will ultimately have to sort it out.

The Chief Justice's decision shows greater clarity of thought, but it would basically allow the application of qualitative orders from foreign jurisdictions apply here, unless the same narrow tests that apply to money judgments are met.

There are a couple annoying things about the Chief Justice's decision. First, she refers to Law Reform Commission recommendations (which, I understand, are actually limited to inter-provincial application of qualitative judgments) as reasons for judges to change the law. On the contrary, if an issue is the subject of potential legislative reform, and the legislatures have not acted, that suggests there are policy reasons not to act, and the whole thing should be left with the political process. McLachlin's discussion here reminds me of how she used class action legislation in some provinces to force class actions on the provinces that had deliberately refrained from enacting them.

The other annoying thing is the assertion that constitutional values of privacy (and, in this case, freedom of speech) don't matter in civil actions, since the coerced disclosure is to sworn private enemies, rather than the state. It strikes me that this makes things worse, not better. I might be worried about what some bureaucrat will do with my personal information, but I can probably rely on the reality that he or she will probably be more interested in coffee breaks and Solitaire. Giving my personal information to profit-maximizing corporations, particularly ones I have a dispute with, is more problematic, and should only happen when there has been a clear legislative judgment to require me to do it.

Finally, it is extremely odd that both justices take the principle of "comity" as the dominant one in private international law, but fail to give any weight to the fact that American courts would never domestically enforce a non-money judgment of a Canadian court.

Anyway, the private international law revolution stalled a bit on Friday, which is good, but will probably be temporary relief.

Case Comment of Pro Swing Inc. v. Elta Golf Inc.

Photo of Madam Justice Deschamps credited to Phillipe Landreville, Supreme Court of Canada collection

Update: An ectomorphic take on Pro Swing can be found here. Andy makes the point that the civil law judges voted against bringing the common law into line with their own.

Sunday, November 19, 2006

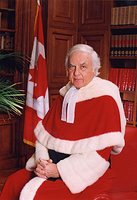

The Chief Justice as Superstar

Andy the Ectomorph observes (I think correctly) the much-enhanced public role of Chief Justice Beverly McLachlin in comparison with her predecessor Antonio Lamer, and asks what it all means.

Its superempowered constitutional role has created an institutional need for a politically-savvy and media-conscious figure to do public relations for the Court. The need has existed for a while, but Uncle Tony was just not equipped to provide it: when he spoke extra-judicially and publicly, the result was always embarrassing for the Court Party. Brian Dickson wasn't as bad as Lamer, but he had the same corporate lawyer's incapacity for political communication that we saw in John Turner. Going back even further, Bora Laskin was more successful as a public figure than on his own court, where he was in a permanent minority with Spence and Dickson (L-S-D): in those days, it was really Ronald Martland, as leader of the conservative-Quebec alliance, who was the Chief Justice.

The current Chief Justice, though, is completely and utterly suited to be a public advocate for the court's role. In her own jurisprudence, she combines substantive caution and moderation with a consistent support for expanding the court's role. And she clearly has political skills. Maurice Vellacot was substantively in the right in his conflict with her last spring, but there can be no doubt that he had his political butt handed to him.

I agree with Andy that the Beverley McLachlin is, in many ways, an admirable judge. She is open-minded and pragmatic. And she has a superhuman work ethic. Unfortunately, though, her advocacy skills are put to the benefit of the institutional interests of the court and of the legal profession. That's perhaps what you would expect, given her role, but it could work against the interests of the country. The Harper government would be ill-advised to underestimate her.

Tuesday, November 14, 2006

Radical Tories A Generation On

At my local bookstore, I noticed that Radical Tories by Charles Taylor (the journalist son-of-E.P. Taylor, not the philosopher or Liberian dictator) has been re-released.

Taylor has chapter-length sketches of a number of Canadian intellectuals and politicians he lumps together as, in some sense, “red Tories”: Conservative historian Donald Creighton, Liberal historian W.L. Morton, Liberal senator Eugene Forsey, nationalist poet Al Purdy, federal Conservative leader and underwear heir Robert Stanfield, dimunitive Toronto mayor and Conservative cabinet minister David Crombie and pessimistic political philosopher George Grant. Only Crombie is still alive.

The tendency Taylor was trying to define is a bit vague: nationalistic, anti-libertarian and supportive of British North American traditions, but not particularly programmatic. Taylor writes biographical and journalistic profiles, not manifestoes, and he says little about the issues of that day or this. There is not much about Quebec separatism, concrete economic policies or the Cold War.

My favourite bit is when Taylor takes George Grant to Woodbine race track, where he says something incredibly pompous, much to the disgust of Purdy.

“Red Tory” was never a well-defined term, and it never described a particularly influential trend in our political life. It has come to mean the opposite of what Grant or Taylor intended. Today it is commonly used to refer to someone who has no trouble either with the global market or Trudeau’s attempted erasure of traditional English Canada, someone pleased both with Trudeau’s Charter of Rights and Mulroney’s free trade agreements, a libertarian lite. Crombie fits in with this more contemporary meaning of red Tory, but there is little evidence that he (or Stanfield) ever wanted to take some doomed Grantian stand on behalf of “our own” against the twin evils of corporate capitalism and post-ethnic post-Christian “rights-talk” liberalism.

The one "practical" politician clearly inspired by Taylor’s book was the Quixotic David Orchard. Orchard took seriously the idea of an economically nationalist progressive conservatism, and he and his followers briefly had significant influence in the post-Kim Campbell pre-fusion Progressive Conservative party. Orchard will be remembered, of course, for agreeing to support the egregious Peter Mackay in return for his signed promise not to liquidate the PC party, a contract cynically negotiated with the connivance of Brian Mulroney and as cynically breached.

I found Taylor’s book interesting as a teenager, before falling under the spell of doctrinaire Marxism. I no longer find economic nationalism and statism particularly appealing. But I recognize something of value in what Taylor was trying to do.

As Grant recognized and bemoaned, we British North Americans always had a profoundly liberal, as well as monarchical and Christian, tradition. We cannot counterpose to the religion of progress – in either its libertarian or egalitarian guises – with the Syllabus of Errors, or some idealized, reactionary medievalism. Our tradition – like it or not – is one of commercial and personal liberty, of technological progress and of relative social egalitarianism.

But our tradition was not one of economic determinism, on the one hand, or a belief in the infinite malleability of human nature on the other. Our founders recognized that economic issues (best handled, they thought, with a mixture of internal laissez-faire and government-subsidised infrastructure development) could never be as destructive or as important as religious and ethnic ones. They did not believe that people would forego their particularistic loyalties, but they did think that those differences could be managed within a framework of British institutions.

Since Taylor wrote, what he loved has been bashed both from the left (in the form of multiculturalism and the Charter) and from the right (in the form of the Free Trade Agreement and the Washington Consensus). All of these can point to some roots in the English Canadian tradition. But the true believers in both versions of progress are united in their embarrassment at the remnants of that tradition.

It is pretty easy for what Taylor was sketching to fall into the traps of nostalgia, racial-exclusivity, retrograde gender politics and economic illiteracy. Equally, there are domesticated Canada Council/CBC versions of "Tory" nationalism that are virtually indistinguishable from Annex bien-pensant socialism. And the literalist political example of David Orchard is not encouraging. But I think there's something worth rescuing.

Taylor has chapter-length sketches of a number of Canadian intellectuals and politicians he lumps together as, in some sense, “red Tories”: Conservative historian Donald Creighton, Liberal historian W.L. Morton, Liberal senator Eugene Forsey, nationalist poet Al Purdy, federal Conservative leader and underwear heir Robert Stanfield, dimunitive Toronto mayor and Conservative cabinet minister David Crombie and pessimistic political philosopher George Grant. Only Crombie is still alive.

The tendency Taylor was trying to define is a bit vague: nationalistic, anti-libertarian and supportive of British North American traditions, but not particularly programmatic. Taylor writes biographical and journalistic profiles, not manifestoes, and he says little about the issues of that day or this. There is not much about Quebec separatism, concrete economic policies or the Cold War.

My favourite bit is when Taylor takes George Grant to Woodbine race track, where he says something incredibly pompous, much to the disgust of Purdy.

“Red Tory” was never a well-defined term, and it never described a particularly influential trend in our political life. It has come to mean the opposite of what Grant or Taylor intended. Today it is commonly used to refer to someone who has no trouble either with the global market or Trudeau’s attempted erasure of traditional English Canada, someone pleased both with Trudeau’s Charter of Rights and Mulroney’s free trade agreements, a libertarian lite. Crombie fits in with this more contemporary meaning of red Tory, but there is little evidence that he (or Stanfield) ever wanted to take some doomed Grantian stand on behalf of “our own” against the twin evils of corporate capitalism and post-ethnic post-Christian “rights-talk” liberalism.

The one "practical" politician clearly inspired by Taylor’s book was the Quixotic David Orchard. Orchard took seriously the idea of an economically nationalist progressive conservatism, and he and his followers briefly had significant influence in the post-Kim Campbell pre-fusion Progressive Conservative party. Orchard will be remembered, of course, for agreeing to support the egregious Peter Mackay in return for his signed promise not to liquidate the PC party, a contract cynically negotiated with the connivance of Brian Mulroney and as cynically breached.

I found Taylor’s book interesting as a teenager, before falling under the spell of doctrinaire Marxism. I no longer find economic nationalism and statism particularly appealing. But I recognize something of value in what Taylor was trying to do.

As Grant recognized and bemoaned, we British North Americans always had a profoundly liberal, as well as monarchical and Christian, tradition. We cannot counterpose to the religion of progress – in either its libertarian or egalitarian guises – with the Syllabus of Errors, or some idealized, reactionary medievalism. Our tradition – like it or not – is one of commercial and personal liberty, of technological progress and of relative social egalitarianism.

But our tradition was not one of economic determinism, on the one hand, or a belief in the infinite malleability of human nature on the other. Our founders recognized that economic issues (best handled, they thought, with a mixture of internal laissez-faire and government-subsidised infrastructure development) could never be as destructive or as important as religious and ethnic ones. They did not believe that people would forego their particularistic loyalties, but they did think that those differences could be managed within a framework of British institutions.

Since Taylor wrote, what he loved has been bashed both from the left (in the form of multiculturalism and the Charter) and from the right (in the form of the Free Trade Agreement and the Washington Consensus). All of these can point to some roots in the English Canadian tradition. But the true believers in both versions of progress are united in their embarrassment at the remnants of that tradition.

It is pretty easy for what Taylor was sketching to fall into the traps of nostalgia, racial-exclusivity, retrograde gender politics and economic illiteracy. Equally, there are domesticated Canada Council/CBC versions of "Tory" nationalism that are virtually indistinguishable from Annex bien-pensant socialism. And the literalist political example of David Orchard is not encouraging. But I think there's something worth rescuing.

Friday, November 10, 2006

How Canadian Are You?

Find out here.

The Pithlord got 97%, which is pretty good (or "not too bad" in Canadian). I probably lost the 3% because I refused to say I'd buy my sister a dress at Canadian Tire.

Inevitable Regionalist Bitching Update: I lived in Toronto for six years, so I knew the answer to the "Pizza Pizza" question, but the damn chain doesn't exist in Western Canada! Once again, as in the dark days of the NEP, we have been shunted aside by the damn Easterners and their ...[blah...blah...blah, etc.. you know the drill]

The Pithlord got 97%, which is pretty good (or "not too bad" in Canadian). I probably lost the 3% because I refused to say I'd buy my sister a dress at Canadian Tire.

Inevitable Regionalist Bitching Update: I lived in Toronto for six years, so I knew the answer to the "Pizza Pizza" question, but the damn chain doesn't exist in Western Canada! Once again, as in the dark days of the NEP, we have been shunted aside by the damn Easterners and their ...[blah...blah...blah, etc.. you know the drill]

Ardent for some desperate glory

Every year, the ritual was the same.

The Headmaster read the lists of the school's dead from each world war, and the shorter list for Korea. WASP name after WASP name -- in the Great War, it must have been half the graduates. The letter from the school founder to the "boys," the cheery and sentimental Edwardian voice framed by the easy irony of his death in the trenches a month later. And then the poems: always two, always the same. Wilfred Owen's Dulce et Decorum Est and John McCrae's In Flanders Fields.

I can't remember which year I realized that the two poems were saying exactly the opposite thing, that the two poets would have despised each other. No doubt I was pleased with myself for noticing the first time, and then self-righteously indignant the next times. But at middle age, I suppose my elders were right. Many of them were still of the generation that fought. It really is ambiguous how we break faith with those who die -- whether by failing to take up their quarrel with the foe or by colonizing a gruesome death with noble words.

Owen was the better poet, and had the more lasting impact on his culture. Even in my generation, there are people to whom that old Edwardian idealism speaks. Forty two Canadians younger than me have died in combat since 2002. To them, honour and valour still mean something other than the con game Owen perceived. And I am glad they exist, since we are probably burning up our stores of those virtues, with God knows what consequences when we come to the end of them.

Owen doesn't say anything about why so many men have loved war, why it is so liberating. Freud may not have been a scientist, but how well he understood that feeling, that joy in destruction and in the overthrow of civilization.

But what he gets right is the contrast between the technology and bureaucracy of war -- and the ugliness of death -- with the adolescent notions that get us there.

I have no real idea what my elders thought they were doing with that ritual, whether they were shaming us for our peaceful bourgeois lives or warning us against militaristic folly. They probably didn't know either, and they seemed uninterested in the effect of these things on us.

A surprisingly large number of my class did join the armed forces, especially considering how low prestige and ill-paid it was in those days. They were definitely among the most square. It seemed unlikely that there would be much glory in it then: if a real war came, we assumed we'd all -- civilian or otherwise -- be dead virtually instantly. In the meantime, there didn't seem to be much other than policing duties in Cyprus. Canadian offensive military power was a joke. Still is, I suppose, but the one guy I know from those days who is still in the Armed Forces seems to have seen a lot of violence in a lot of places.

Another group of us spent the next decade marching, getting into fights with obscure far right cranks, workers in resource industries and occasionally the police. When we opposed logging, we learned defence in depth -- when we opposed overseas wars, we seemed to do a lot of marching. Since we all smoked, we had to get our exercise somehow. John McRae would have hated us, and maybe Wilfred Owen would have too. No doubt we avoided taking real risks. But our cowardice mixed with an ardour for desperate glory. And we didn't lack for lies.

For the first time in my lifetime, Remembrance Day comes with a Canadian people aware that we are in a serious war. The old generation of vets that were such a dominating presence in my childhood thins out. Another, much smaller, one is being forged, and may have a lot to say in my middle age.

Even a conservative Anglo-Canadian private school in the 80s could not quite get away with incorporating Kipling into its ritual. But the old bastard managed to combine commitment to his to us misguided loyalties with awareness of how insignificant what he was loyal to ultimately was. So I'll end this year with him and Joe Strummer.

The Headmaster read the lists of the school's dead from each world war, and the shorter list for Korea. WASP name after WASP name -- in the Great War, it must have been half the graduates. The letter from the school founder to the "boys," the cheery and sentimental Edwardian voice framed by the easy irony of his death in the trenches a month later. And then the poems: always two, always the same. Wilfred Owen's Dulce et Decorum Est and John McCrae's In Flanders Fields.

I can't remember which year I realized that the two poems were saying exactly the opposite thing, that the two poets would have despised each other. No doubt I was pleased with myself for noticing the first time, and then self-righteously indignant the next times. But at middle age, I suppose my elders were right. Many of them were still of the generation that fought. It really is ambiguous how we break faith with those who die -- whether by failing to take up their quarrel with the foe or by colonizing a gruesome death with noble words.

Owen was the better poet, and had the more lasting impact on his culture. Even in my generation, there are people to whom that old Edwardian idealism speaks. Forty two Canadians younger than me have died in combat since 2002. To them, honour and valour still mean something other than the con game Owen perceived. And I am glad they exist, since we are probably burning up our stores of those virtues, with God knows what consequences when we come to the end of them.

Owen doesn't say anything about why so many men have loved war, why it is so liberating. Freud may not have been a scientist, but how well he understood that feeling, that joy in destruction and in the overthrow of civilization.

But what he gets right is the contrast between the technology and bureaucracy of war -- and the ugliness of death -- with the adolescent notions that get us there.

I have no real idea what my elders thought they were doing with that ritual, whether they were shaming us for our peaceful bourgeois lives or warning us against militaristic folly. They probably didn't know either, and they seemed uninterested in the effect of these things on us.

A surprisingly large number of my class did join the armed forces, especially considering how low prestige and ill-paid it was in those days. They were definitely among the most square. It seemed unlikely that there would be much glory in it then: if a real war came, we assumed we'd all -- civilian or otherwise -- be dead virtually instantly. In the meantime, there didn't seem to be much other than policing duties in Cyprus. Canadian offensive military power was a joke. Still is, I suppose, but the one guy I know from those days who is still in the Armed Forces seems to have seen a lot of violence in a lot of places.

Another group of us spent the next decade marching, getting into fights with obscure far right cranks, workers in resource industries and occasionally the police. When we opposed logging, we learned defence in depth -- when we opposed overseas wars, we seemed to do a lot of marching. Since we all smoked, we had to get our exercise somehow. John McRae would have hated us, and maybe Wilfred Owen would have too. No doubt we avoided taking real risks. But our cowardice mixed with an ardour for desperate glory. And we didn't lack for lies.

For the first time in my lifetime, Remembrance Day comes with a Canadian people aware that we are in a serious war. The old generation of vets that were such a dominating presence in my childhood thins out. Another, much smaller, one is being forged, and may have a lot to say in my middle age.

Even a conservative Anglo-Canadian private school in the 80s could not quite get away with incorporating Kipling into its ritual. But the old bastard managed to combine commitment to his to us misguided loyalties with awareness of how insignificant what he was loyal to ultimately was. So I'll end this year with him and Joe Strummer.

Far-called our navies melt away;

On dune and headland sinks the fire;

Lo, all our pomp of yesterday

Is one with Nineveh and Tyre!

Judge of the Nations spare us yet,

Lest we forget -- lest we forget!

If drunk with sight of power, we loose

Wild tongues that have not thee in awe--

Such boasting as the Gentiles use

Of lesser breeds without the law--

Lord God of Hosts, be with us yet

Lest we forget -- lest we forget.

From the Hundred Years War to the Crimea

With a lance and a musket and a roman spear

To all of the men who stood without fear

In the service of the King

Before you meet your fate be sure you did not forsake

Your lover may not be around any more.

Thursday, November 09, 2006

What will the Roberts Court do about partial-birth abortion? And about federalism?

The Supreme Court of the United States has been hearing oral arguments in the Gonzales v. Carhart and Gonzales v. Planned Parenthood cases this week. (All the links you could want are here). The case is about the constitutionality of the federal partial birth abortion ban.

The key 14th Amendment issue seems to be whether Congress can come to its own judgment on the issue of whether a particular abortion procedure is medically necessary, and what review the courts should apply. My prediction there is that Roberts-Alito-Scalia-Thomas will agree that a very wide deference is owed to legislative judgments, that Stevens-Ginsburg-Breyer-Souter will say that Congressional judgment is owed little deference, and was wrong here, and that Kennedy will write the opinion of the court saying little deference is owed, but Congress got it right this time. We will see if the crystal ball holds up.

What would I do? Well, unlike people on the left of the abortion issue, I think the conflict-of-interest inherent in a doctor who performs abortions deciding what is medically necessary is a legitimate and important legislative concern. I think this is something the political process should decide.

But which political process? The state or the federal? This strikes me as precisely the sort of divisive cultural/moral issue that should be in the hands of individual states: there is just no need for a single, federally-mandated solution.

It should be noted that the federal partial birth abortion ban is based on the "Interstate Commerce" clause of Article 1, a clause which has been bent out of all recognition by post-New Deal "progressive" jurisprudence, into a pretty much all-encompassing grant of federal power. The Rehnquist court made some baby steps in cutting back on this theory when it comes to non-economic regulation, but except for Clarence Thomas,* there were at best fairweather federalists on that court. It will therefore be interesting to see what Alito and Roberts do.

According to Marty Lederman, John Paul Stevens, the leader of the liberal bloc, was the one to raise the federalism issue in oral argument. He asked how Interstate Commerce could apply to an abortion clinic that does not charge for its services. The Solicitor General cleverly suggested that this issue could only be dealt with in an "as-applied" challenge, since it might be that the federal statute, properly interpreted, would not apply for non-constitutional reasons.

A more fundamental question -- it seems to me -- is whether the federal government should be allowed to regulate something for patently non-economic reasons, just because it might be bought and sold. That strikes me as the punchline to a reductio ad absurdum, but sensible Americans tell me that even the wild-eyed federalists on the court believe it.

Interestingly, though, Justice Scalia is on record (non-judicially) saying the federal government has no jurisdiction over abortion:

I would hope that all of Thomas, Kennedy, Alito and Roberts would agree with this, in which case the federal law ought to be considered unconstitutional by everybody.

*Thomas is apparently not present for the oral hearing because he is sick, but will rule in the case. This is a bit shocking to my own lawyerly sensibilities, so I wonder if my American readers can tell me whether this is common in American courts.

The key 14th Amendment issue seems to be whether Congress can come to its own judgment on the issue of whether a particular abortion procedure is medically necessary, and what review the courts should apply. My prediction there is that Roberts-Alito-Scalia-Thomas will agree that a very wide deference is owed to legislative judgments, that Stevens-Ginsburg-Breyer-Souter will say that Congressional judgment is owed little deference, and was wrong here, and that Kennedy will write the opinion of the court saying little deference is owed, but Congress got it right this time. We will see if the crystal ball holds up.

What would I do? Well, unlike people on the left of the abortion issue, I think the conflict-of-interest inherent in a doctor who performs abortions deciding what is medically necessary is a legitimate and important legislative concern. I think this is something the political process should decide.

But which political process? The state or the federal? This strikes me as precisely the sort of divisive cultural/moral issue that should be in the hands of individual states: there is just no need for a single, federally-mandated solution.

It should be noted that the federal partial birth abortion ban is based on the "Interstate Commerce" clause of Article 1, a clause which has been bent out of all recognition by post-New Deal "progressive" jurisprudence, into a pretty much all-encompassing grant of federal power. The Rehnquist court made some baby steps in cutting back on this theory when it comes to non-economic regulation, but except for Clarence Thomas,* there were at best fairweather federalists on that court. It will therefore be interesting to see what Alito and Roberts do.

According to Marty Lederman, John Paul Stevens, the leader of the liberal bloc, was the one to raise the federalism issue in oral argument. He asked how Interstate Commerce could apply to an abortion clinic that does not charge for its services. The Solicitor General cleverly suggested that this issue could only be dealt with in an "as-applied" challenge, since it might be that the federal statute, properly interpreted, would not apply for non-constitutional reasons.

A more fundamental question -- it seems to me -- is whether the federal government should be allowed to regulate something for patently non-economic reasons, just because it might be bought and sold. That strikes me as the punchline to a reductio ad absurdum, but sensible Americans tell me that even the wild-eyed federalists on the court believe it.

Interestingly, though, Justice Scalia is on record (non-judicially) saying the federal government has no jurisdiction over abortion:

[I]f a state were to permit abortion on demand, I would -- and could in good conscience -- vote against an attempt to invalidate that law for the same reason that I vote against the invalidation of laws that forbid abortion on demand: because the Constitution gives the federal government (and hence me) no power over the matter.

I would hope that all of Thomas, Kennedy, Alito and Roberts would agree with this, in which case the federal law ought to be considered unconstitutional by everybody.

*Thomas is apparently not present for the oral hearing because he is sick, but will rule in the case. This is a bit shocking to my own lawyerly sensibilities, so I wonder if my American readers can tell me whether this is common in American courts.

Wednesday, November 08, 2006

Dems take House and probably Senate; I become more insufferable than ever

Well, I'm going to go to bed without knowing George Allen's litigation strategy, but Webb is up by 12,000 and it appears that Montana and Missouri are in the bag. Result will be 50 Democrats (including Lieberman), 49 Republicans and one Vermont socialist. Advantage Pithlord.

+30 for the Democrats in the House looks about right too.

Yes, yes, I know that I'm creating bad karma here. But it's a great night. The American people have rejected the Peronist politics of jingoism and fiscal incontinence. I agree with the commentators who are saying that the US electorate has not embraced "liberalism." Just as there was nothing particularly conservative about the party of imperialism and insolvency, there is nothing particularly progressive about the desire to be rid of them. But it's good to see all the same.

+30 for the Democrats in the House looks about right too.

Yes, yes, I know that I'm creating bad karma here. But it's a great night. The American people have rejected the Peronist politics of jingoism and fiscal incontinence. I agree with the commentators who are saying that the US electorate has not embraced "liberalism." Just as there was nothing particularly conservative about the party of imperialism and insolvency, there is nothing particularly progressive about the desire to be rid of them. But it's good to see all the same.

Sunday, November 05, 2006

AstraZeneca -- Thumbs Up

Can a patent drug manufacturer prevent generic drug manufacturers from producing a drug based on an expired patent by taking out "related" patents?

On Friday, the SCC answered this question with a big "no."

That was the right call. The alternative would have been to eviscerate the time-limited nature of the patent, which would be a very bad idea indeed.

On Friday, the SCC answered this question with a big "no."

That was the right call. The alternative would have been to eviscerate the time-limited nature of the patent, which would be a very bad idea indeed.

Case Comment of AstraZeneca Canada Inc. v. Canada (Minister of Health), 2006 SCC 49

Friday, November 03, 2006

Flaherty Kills the Income Trust: Right Thing to Do, But No Good Deed Goes Unpunished

The big political/economic story in Canada, of course, is the Minister of Finance's announcement on Halloween that the Government is going to eliminate the favourable tax treatment of income trusts relative to corporations. The general corporate tax rate is to drop by half a percentage point to make the change (statically) revenue-neutral.

The predictable reaction of the markets was a $25 billion selloff. If your a Canadian and have any investments at all, you almost certainly lost money this week. To make matters worse for the Tories, they specifically promised not to do this in their election platform.

From a policy perspective, this was the right thing to do. Under existing law, the income trusts are tax-efficient, but they are inefficient corporate governance vehicles. The alternative to doing this would be to abandon corporate income tax altogether, and just tax income in the hands of individuals. That wouldn't be an entirely awful idea. There is much that is economically illiterate in the NDP call to faire payer les corporations -- since corporations are fundamentally legal fictions, they can't ultimately bear the tax burden. Only individuals can. But a corporate tax does effectively tax foreign investors in Canadian enterprises and prevents a simple form of tax deferment and tax splitting.

But if the Tories have done the right thing, they are going to pay a political price for it. John Ibbitson's claim to the contrary is not convincing.

First of all, it is hard to imagine a change in government policy with such a direct, immediate effect on the finances of millions of potentially Conservative voters. A good or bad economy may or may not be the work of the party in power. The loss of value in the markets on Tuesday clearly was.

Second, it is easy to point out that the Tories went back on a promise, just as Chrétien did with the GST. From a policy perspective, Chrétien was absolutely right not to eliminate the GST, but a promise is still a promise, and it did him some harm. This will probably be worse, since there is no deficit to point to in explanation, and since the effect is so immediate.

Ibbitson's response is that by getting this out of the way now, Harper can recover later. This analysis misses two points. First, a quick election, before the Grits have their act together, might have been a good deal for the Tories. They don't have that option now.

More subtly, this changes the whole dynamic of a minority Parliament. Harper could act as if he had a majority only because the opposition didn't really want to defeat him and go to the polls. We'll see what Angus Reid has to say, but if it's bad news for the government, then the opposition has the upper hand in the game of chicken that a minority Parliament inevitably is.

Politically, it surely would have been better to tie this announcement to much broader tax relief than Finance is proposing now. But the Government still doesn't know what kind of deal it might make on the diséquilibre fiscale. So it is stuck.

Update: The early empirical evidence isn't kind to my instant political analysis. It appears the Tories are up in the Ipsos Reid poll taken immediately after the Income Trusts decision.

The predictable reaction of the markets was a $25 billion selloff. If your a Canadian and have any investments at all, you almost certainly lost money this week. To make matters worse for the Tories, they specifically promised not to do this in their election platform.

From a policy perspective, this was the right thing to do. Under existing law, the income trusts are tax-efficient, but they are inefficient corporate governance vehicles. The alternative to doing this would be to abandon corporate income tax altogether, and just tax income in the hands of individuals. That wouldn't be an entirely awful idea. There is much that is economically illiterate in the NDP call to faire payer les corporations -- since corporations are fundamentally legal fictions, they can't ultimately bear the tax burden. Only individuals can. But a corporate tax does effectively tax foreign investors in Canadian enterprises and prevents a simple form of tax deferment and tax splitting.

But if the Tories have done the right thing, they are going to pay a political price for it. John Ibbitson's claim to the contrary is not convincing.

First of all, it is hard to imagine a change in government policy with such a direct, immediate effect on the finances of millions of potentially Conservative voters. A good or bad economy may or may not be the work of the party in power. The loss of value in the markets on Tuesday clearly was.